5 year, 10 year, 25 year plans – I don’t see the point of them, and I see how important they are.

The problem with long-term thinking is that plans change. The environment in which any human operates isn’t a static one. And so to say, “In 25 years, I’m going to travel the world, and do all the things I never got to do while I was working” seems dangerous to me. Yet, it’s the overarching narrative of my parents’ generation – work hard now, enjoy yourself later. Of course, later may never come and, even if it does, it may coincide with a 3-year travel ban because of a global pandemic. As the old saying goes, ‘You just never know.’

Conversely, the problem with short-term thinking is that it’s very difficult to build something bigger or something beyond what we’ve got right now. If all I do is think about tomorrow, I wouldn’t save money because, well, tomorrow may not come so I better spend it now. If all that mattered was getting to next week, my diet would contain many more chips and far less broccoli.

In both cases, we’re making bets. The long-term thinker is making a bet that things will be fairly predictable over 25 years in order to enable their 25-year plan. The short-term thinker, on the other hand, is making a bet that tomorrow may be vastly different from today and so it’s better to strike while the iron’s hot and do what you want to do now. But, maybe there’s a middle ground.

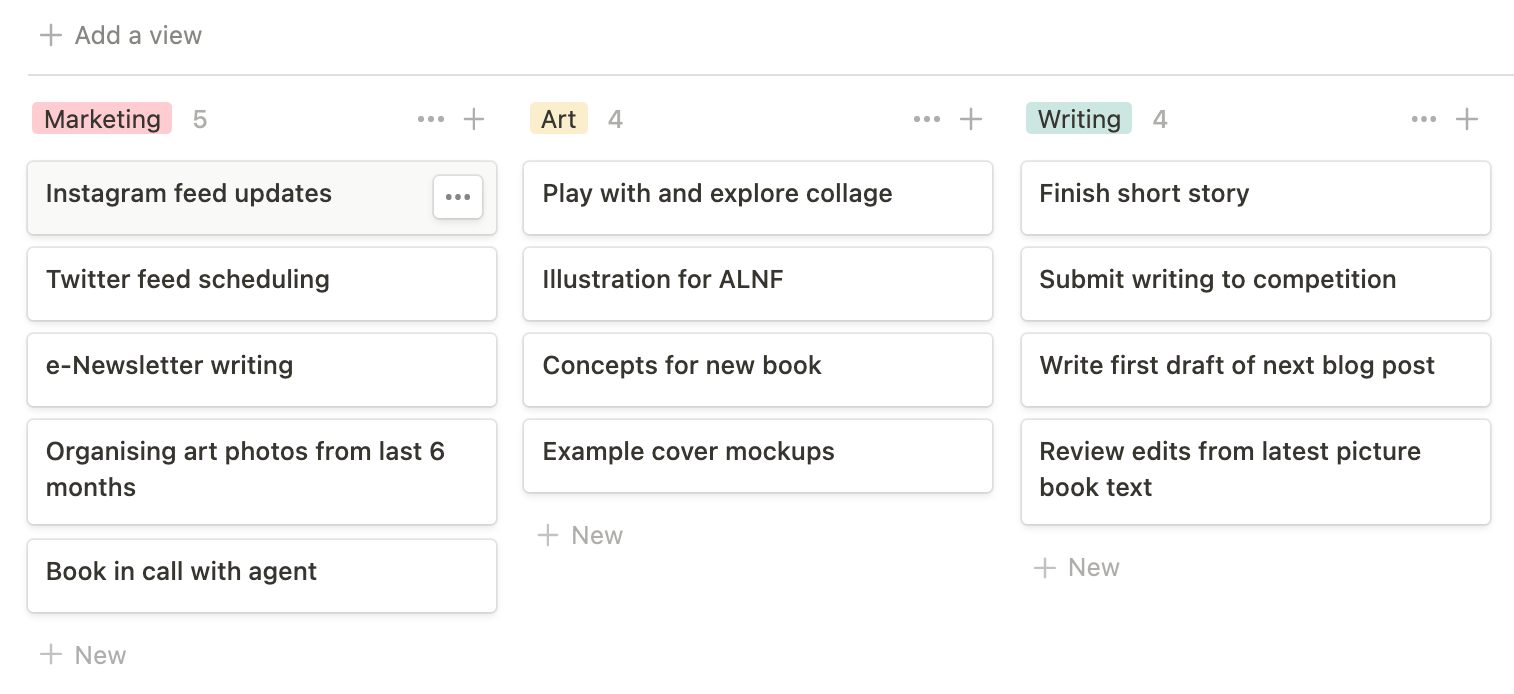

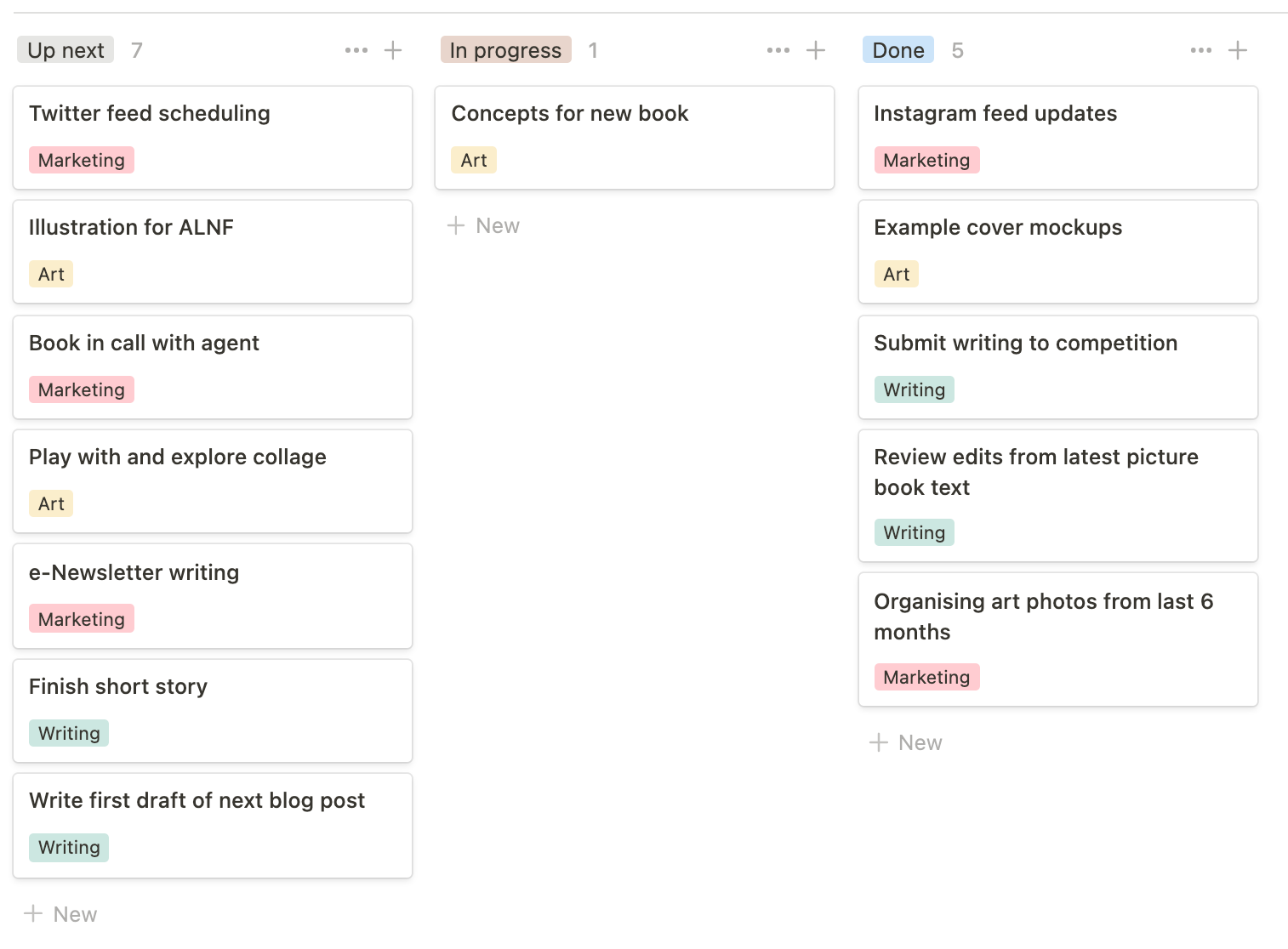

Incremental planning

Maybe there’s a better way to make bets? If we have more certainty in shorter timeframes and less certainty across longer horizons where does that leave us?

The longer the timeframe, the less specific or abstract the goal. Many of my parents’ generation planned on ‘visiting country x‘ when they retired. Or ‘driving around Australia.’ But, who knows whether driving will even exist in 25 years given the way automation is going. And who knows what political turmoil any given country will be in 25 years.

Outcome over output

For long term plans, thinking about outcome over output seems to be the right way to go. The trick here is to ask yourself, “Why that country?” or “Why driving?” If we understand the motivation behind our intentions, we may be able to use the concept of equifinality to satisfy our needs without being so specific. Maybe the goal of both of those things is really to see places that are simply different to the ones we inhabit everyday. There are many ways to achieve that, and you may not need to wait 25 years.

Once we know the less specific goal and the reasons why we have it in the first place, we can make smaller goals, based on closer timeframes, that still progress towards the larger picture. The idea of seeing different places can start right now. For example, during the constraints imposed on us by a pandemic, we’ve travelled to Victorian towns like Maldon, Benalla, and Gippsland – these are all places we’ve never been before. It scratches the novelty itch, and we build empathy for people who are not like us. We’re already achieving a version of the 25 year plan but it’s happening right now.

With an outcome mindset, and a little incremental planning, we become far more adaptable and resilient. We can still fulfill our needs allbeit in a perhaps a slightly less than ideal or different way than we may have intended or imagined.

What’s this got to do with art? Well, artist’s goals are usually, “I want to make a living from my art” or “I don’t want to compromise on my vision.” But, when we give ourselves time and introspect on the reason why we want to make a living from our art, it’s usually because the way we’re currently making a living is stressful, or tiring, or boring, and what we really want is for those feelings to go away or, at least, be reduced somehow.

I find the idea of blending my way to make money with my ability to produce art completely frightening for a number of reasons. Because of this, and using the concepts above, I’ve been able to balance a job that I’m lucky enough to find interesting, with ‘some picture book work on the side.’ I’m not particularly stressed or bored living this way, so maybe I’ve already got what I need without needing to commit to being a full-time artist. Maybe the tweaks we need to make to live a less stressed more fulfilling life aren’t really as big as throwing it all in and leaving a different life behind?