We need a more complex discussion about that word – Diversity – and how those of us with a platform in literature can shape a more equal world. As humans, we’re pretty lazy, so we like short words that can stand in for complex and difficult-to-articulate things. I’m concerned about how I’ve seen it used, particularly in publishing, where we refer to people as ‘diverse authors’ when what I think we mean by this is “Authors that are members of groups who have been historically under-represented in our media or historically discriminated against.” Why is it so hard to just say what we mean?

When thinking about how to represent “diversity” in my own work, children’s literature, it’s no less complex. I’m often paralysed by fear and uncertainty about how I’m supposed to represent under-represented groups or those who have been historically discriminated against, especially as someone who isn’t from those groups and has a whole lot of privilege baked into my life.

There is no silver bullet here because it’s about culture change – whether we like it or not, that takes time. We need efforts at systemic and individual levels, working together over time, to listen to one another, learn from one another and, ultimately help one another.

I’ve noticed a few different approaches to how people are including diversity into their work, or how they’re talking about it. “Randomness” is one way – the idea that if we ignore social and historical context, notions of power and hierarchy, we’ll move to a world with more equity more quickly. There is of course the ‘representing reality’ thing, where we use data and research to inform our choices and remove ‘unconscious bias’ about how we represent the under-represented. And yes, while these are good ideas, they’re not good enough because it doesn’t reckon with how culture change actually works.

Diversity as ‘randomness’

Life is chaos, but we don’t want it to be. True randomness unsettles. It means things are unpredictable, unstable, uncertain. Instead, we wrap narratives around randomly occurring events using abstract correlations misinterpreted as causation to make sense of it all. We seem to call that narrative a life.

When the iPod first came out, it’s ‘shuffle play’ wasn’t acting like we wanted shuffle to act. It began as a truly random selection of songs, not ‘expected random’. This meant you would sometimes hear the same song two or three times in a session. What was truly random was seen as repetitive. We don’t *expect* random to repeat, so when it does, something feels broken. What we think we want when we say random is variety; a sort of controlled-random. That’s more difficult in programming terms, but it’s how we expect the world to behave. This phenomenon is the same with everything, especially diversity in literature.

Whenever I’m making a picture book, the characters don’t come from nowhere, they have to be designed. How much diversity should be in a country town that I’m designing? I could generate, at random, characters with certain attributes; skin colour, hair colour, eye colour, body type, clothing, etc. If it was truly random, it’s quite possible that in a country town, I would end up with a town of black people with blond hair, a bull-fighter, opera signer, french pastry chef and a class full of kids from Asia and Africa. By the same token, a truly random town could just as easily turn out to be an all-white, Christian, meat-and-potatoes eating population.

Whilst these are truly random, just like life, they don’t feel ‘realistic’.

What is realistic diversity?

The world we live in didn’t just appear. It has thousands of years of biases and discrimination built into it, at all levels – political, social, economic, religious. Whether it’s right to have done so isn’t what I want to focus on. Rather, we have to recognise we are grouped and categorised by where we live, how much money we have, how able-bodied we are, the colour of our skin, and plenty more. A ‘random’ approach to diversity, then, or, in other words, one that ignores these factors of segregation and inequality, isn’t the solution. We need to see the inequality in order to address it.

The other complicating factor is that my version of diversity will be different from another’s – especially a publisher, or a co-creator. Our own lives are biased by the factors I’ve already mentioned and that means we’ve interacted with certain groups and not with others across those political, social, and economic spectrums. For example, the primary school I attended was very mixed in race: Chinese, Italian, Greek, Vietnamese, Lebanese etc. But we were all able-bodied. We lived in the same group of suburbs, and so we had similar economic contexts in which our parents operated, also. In some ways, we were very diverse, and in others, not so. One or two suburbs over and those kids are living completely different lives.

If bias is baked in, something that’s completely unavoidable, then trying to increase the representation of historically-discriminated groups in our literature can’t just come from within us. We need objective data. Well, as objective as we are able to get.

What is data-driven diversity?

Just pause for a moment. Try to answer the question: how many people in Australia live with a disability?

Chances are, if you grew up in a place that had one or more people with a disability, you’ll guess a much higher percentage than if you didn’t. My guess was about 2-3%.

According to the Australian Network on Disability, 4.4 million Australians have some form of disability. Just to be clear, that’s 1 in 5 people, or in percentage terms, 20%. A far cry from my paltry biased number of 2-3%. My entire upbringing was around able-bodied people so, of course, I’d expect that there are less of them in the world.

Now, when you think “disability”, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? For me, it was “wheelchair”. Well, it turns out that only 4.4% of people with a disability in Australia use a wheelchair. 4.4%! But it’s the first thing that came to my mind? I expected at least upwards of 30%. Included in the definition of disability are hearing loss (30,000 people), vision loss (357,000 people), depression/anxiety, and arthritis amongst other conditions. source

So, there’s a lot going on here, but here are a few of the important points we need to consider:

- There are many minority groups in Australia. At 4.4m, disabled people are one of them but that’s just one of many, and it depends on how you cut the data, just like in my primary school. For example, according to census data, 30% of Australians are foreign-born. So they’re a minority, too. So, too, are our indigenous Australians within that context. But then, when you break any group down across race, politics, religion, and so on; you will find a majority and a minority in every facet of our lives.

- Not all minorities have been historically-discriminated against, nor have they been under-represented in our media. What I mean by this is that humans are pretty clever at creating a context that ensures we can identify as a minority group if it suits us. For example, Pentecost makes up 2.1% of all Christians in Australia according to 2016 census data. By that measure, they are a minority. But, in a National context, where Christianity represents 52.1% of the total population, they are part of a bigger religious majority. This is especially important when you consider the laws that govern us have been informed by Christian values more than any other – there is a significant advantage to being a Christian in Australia right now, whether a Christian person knows that or not. No, it’s better to ignore the idea of quantitative comparison when we say ‘minorities’ because what we really mean when we say minorities are groups that have suffered significant, perpetual, & historical discrimination based on gender, colour, religious beliefs and physical ability: women, people of colour, and disabled people are good examples.

- We don’t live according to data, we are the data. Our messy day-to-day experiences shape our view of the world. Because of this, we are inherently, unavoidably biased. For example, in doing research for this article I discovered that there is a greater population of Nepalese people in Australia than American. I’ve never met a Nepalese person in Australia, but I know plenty of Americans, so it’s a surprise to me. That doesn’t make me a bad or judgey human, it’s just my experience. But also, because I’m aware of my narrow view of the world, it’s also unsurprising that I could be wrong. It doesn’t make me an inherently bad human, it’s just a factor of the life I’ve led.

- We have an existing social, political, economic, and moral landscape that we’ve inherited and it will continue to shift with culture over time. Our world is shifting gradually and constantly based on our actions and events we participate in everyday. Yes, it’s difficult to ‘keep up with what’s politically correct’ but it also provides an opportunity for us to exert effort toward making a more equitable world.

So, in place of a truly random approach to including ‘diversity’ in my country town, the easy solution would be to take a purely data-driven approach to creating it instead. I could look up stats: economic and racial breakdowns of residents in a typical country towns of Australia, and draw what I find. After all, that’s just real, right? It takes my own personal bias out of it so doesn’t that make it better? But, here’s where stereo-types and existing inequity become problematic.

The value and danger of stereotypes

If I take a truly data-driven approach to creating my country town, I might get some diversity, yes: I could draw a Nepalese family (but maybe not two?). I could include some disabled people (maybe a blind person instead of one in a wheelchair?), probably a fair few white people. But, given this is a country town, when you look at the data, they’d probably *mostly* be of a certain economic disposition and class, which isn’t very diverse. That’s all well and good, but then I need to work out how to portray all of this to the reader. And so we arrive at stereotypes.

Picture book makers rely on stereotypes. If I need to tell the reader that a person is a doctor, I’ll probably give that character a stethoscope. If I want to tell them they’re a plumber, maybe some overalls and a wrench? Jobs are one thing, but what about ethnicity? What are the visual signals for a person from Nepal? Or America? What about economic class? Do people in this country town eat ‘healthy’ food (salads etc) or do they consume ‘junk’ (chips and pies). What cars do they drive? What sort of houses do they live in? Is there a rich part of the town and a poor part? How ‘nice’ is the main square: clean and pristine or dirty and trash-filled? What job should the black person have – the town sweeper or the School Principal?

Each and every visual signal we provide to the reader communicates the racial, economic, social, religious, and political class of the people who inhabit this made-up world. Will the reader even recognise that it’s a country town if I don’t use some stereotypical imagery? How many people should wear flannel shirts? Should wildlife roam the streets? Should the roads be tarred or dirt? Do the kids wear blazers and boaters to school or polo shirts and shorts? Do they have blackboards or smartboards there? You can see the problem. Representing ‘reality’ while considering the world we ‘want’ to exist is tricky. The good thing is, we have the Overton Window to help us.

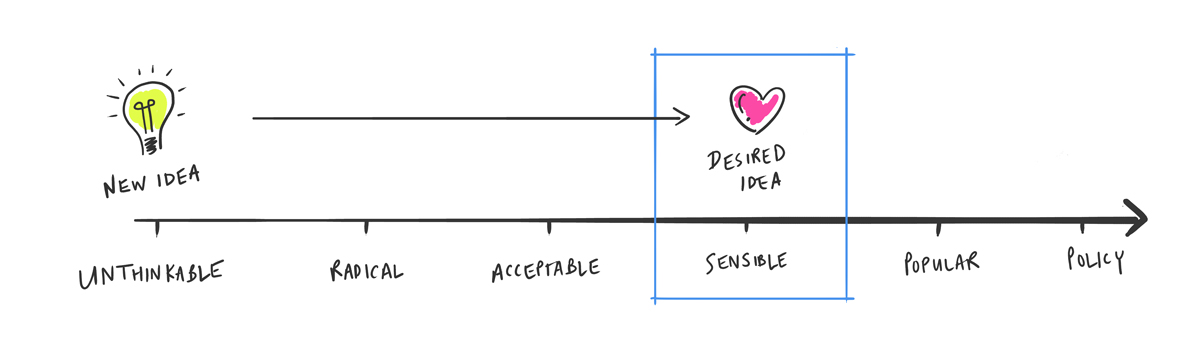

The Overton Window & plausible diversity

The Overton Window, named after Joseph P. Overton, is the range of ideas accepted in the mainstream population at any given time. New ideas that are introduced to the culture are often considered ‘unthinkable’ when they first emerge. For example, the idea of international flight in the early days of airplanes that could only travel a few kilometres was ‘unthinkable’. Over time, that same ‘unthinkable’ idea moves through a spectrum from unthinkable to radical, then acceptable, then sensible, then popular. And here we are flying around the world with ease.

A more political example of The Overton Window: the growing acceptance, in some cultures, of homosexuality. Once an unthinkable, punishable ‘offence’ in some cultures, over time it has moved toward something acceptable, most obviously with the recognition of gay marriage in some countries.

What’s this got to do with picture books? Well, it’s that diversity and equality in picture books (or any literature) isn’t an overnight fix. Ideas that move from the ‘outside’ into the mainstream, take time.

When I think about portraying diversity or equality in my books, I’m not attempting to cram each page, or scene, or country town full of as much diversity as possible in an either truly random way or somewhat controlled data-driven way. I’m not trying to make each and every character it’s own political statement. To do so fails to reckon with The Overton Window. A country town without a single white-person, or one that’s full of fancy cars where everyone eats salad is, to a reader, ‘unthinkable’ or unrealistic, because it’s not what their biases tell them is a ‘country town’. When fiction is living in that ‘unthinkable’ part of the spectrum, it’s far more difficult for a reader to build empathy with the the environment that we’re trying to create.

What we need to shoot for isn’t ‘unthinkable’, but ‘plausible’. We need to continue to shift The Overton Window, book-by-book, publisher by publisher, in subtle but meaningful ways. An accurate representation of the world we have right now is not the answer because we know it’s full of inequity already. The role of books, and literature in general, is about helping us grow as a culture, not stay the same, it’s to help us picture a world, literally, that we want to head toward. Once we make that world, the data follows.

Depicting diversity in practice

So what does good diversity look like in an Australia country town? Well, I’ve arrived at a few principles to keep in mind when I’m designing these worlds. They’ll continue to evolve as a I talk to more people and grow as a human, but perhaps they’ll be helpful to others, right now:

- Depict at least one historically-discriminated-against or under-represented group in every book. It doesn’t need to be a single character, and a character may be a member of multiple groups.

- Ensure that the character/s from number one are doing meaningful work. This means they aren’t a background character but, instead, they are in a position of power and they inherit everything that that comes with that: self-determination, authority, social importance, and influence.

-

Consider economic, social, political, religious, and ethnic domains of diversity. Accept that my view of diversity is itself biased. Ask questions of your characters and environments across all potential facets of discrimination, power and hierarchy:

- Economic: What clothes do they wear? What sort of house do they live in? Do they eat ‘healthy’ food or ‘junk’ food?

- Social: What gender are they? Who are they friends with? Where do they socialise?

- Political: What do they believe? Which side of politics do they lean on? What activities, iconography or visual aids denote left-leaning versus right-leaning in our current culture?

- Religious: What do they believe? Do they ‘wear’ their religion? What do they carry? What do they read? What’s in their house?

- Ethnic: What colour is their skin, hair, eyes? What clothes do they wear? What cuisine do they enjoy (and don’t enjoy)?

- Consult the data, don’t be driven by it. We are biased beings. If we’re going to include ‘diversity’ into our books, we need to make sure we’ve got an objective view of what diversity is. What does ‘disabled’ mean? What does ‘foreign’ or ‘multi-cultural’ mean? What does rich and poor really mean? These questions aren’t exhaustive, there are many others, but they’re incredibly important to consider to ensure we’re challenging ourselves and using the platform we have in the most positive way possible.

- Listen to ‘the other’. Here I am, yet another white person telling the world what I think of ‘diversity’. In the end, I’m not the Nepalese person, or the Tamil refugee. I don’t actually know what it’s like to inhabit this world as someone who isn’t me. So what’s the answer? Simple. Ask. Seek counsel from people who aren’t you. People outside of your social circle. Collaborate and elevate their voices. The world is a big place and the under-represented want every opportunity for better representation. All we have to do is listen.

- Ask yourself, but more importantly, ask the people from the worlds you’re trying to represent, is it plausible and not unthinkable? It’s OK to make your main character white, rich, and Christian if that’s who they are; but that’s the thing, do they need to be? Is it plausible not unthinkable that your School Principal Character could be a black person? Could your plumber be non-binary? Could your doctor dress more like the visual stereotype of a farmer (flannel and dungarees) because, in many country towns, they may not wear white coats and stethoscopes, anyway? Maybe your country town baker is Muslim and makes the most beautiful middle-eastern inspired cakes?

Like the questions I pose, these principles aren’t exhaustive, but they’re a start. They’ve served me well so far and if you’re clever, you’ll find them in my books from the very beginning, even if you may not have noticed them before.

A final example: Round and Round The Garden

I have a new book coming out in February, it’s an addition to my Classic Aussie Nursery Rhyme Series. It’s not a seminal master-work, nor is the idea of if it particularly innovative. It is, at it’s most basic, just a cute nursery rhyme story for 0-3 year olds. Banal. But having consulted the data and listened to disability advocates about the support they need in the world for normalising their condition by people like me – banal, it turns out, is an immense catalyst for change. If there’s ever a time to introduce young minds to the reality of the world we live in where 4.4 million Australians have a disability, it’s through a book like this.

Yes, she’s white. But I ask, could I have put a black female in a wheelchair without making it ‘unrealistic’? Could this character have been from 3 historically-discriminated groups simultaneously? Maybe. But I’ve got the The Overton Window in mind here. For what it’s worth, I had to fight relatively hard for even this representation of diversity. In the end, I’d rather have the book in 10,000 homes because what it’s about is two siblings having a great old time on their wheels, than have a child and parent walk by it in the store because it’s just another obvious political statement or attempt at ‘token diversity’. And anyway, the book doesn’t indicate whether she’s permanently disabled or not… what did you assume?

Links to important voices

The only way we’ll begin to see through our privilege is if we listen to people from marginalised groups. These two talks, which I was lucky enough to see in-person, have and will continue to shape the way I view the world. They were massive influences for this book and my purpose as a tall, white, male author/illustrator of children’s literature.