In one of my first jobs I had a crappy manager. They were disorganised, impolite, inefficient, and well, generally, unkind. I wasn’t happy there and suffice to say when the time came, I moved on.

It’s easy to look at an experience like that – one that lasted 2 years – and think, “What a waste of time. I could’ve done so many more things that would have been better for my physical and mental health, as well as my career.” But that experience was transformative in one very important way; I started to understand what bad looked like.

Knowing what bad looks like means we’re still learning. In subsequent jobs since my first, I’ve filtered potential workplaces based on the signals I saw in my first one. I know the sorts of behaviours that denote disorganized, impolite, inefficient and unkind workplaces, and when I see those behaviours, I walk the other way. Not only that, but I ensure my own behaviour doesn’t mimic those things either.

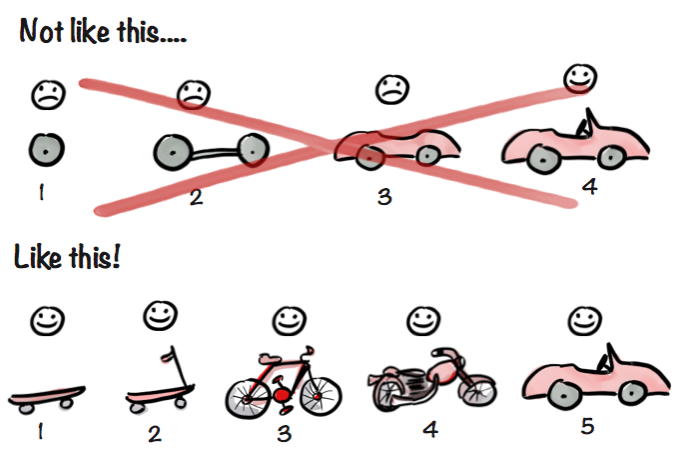

What’s this got to do with art? Well, making bad work in art is inevitable. However, to know what bad looks like, we have to take the leap and make the work, even at the risk of getting it wrong. We have to make the work in order to learn from it and apply it to the next work. I’ve made many mistakes in my pursuit of expressive, joyous watercolour work. I have pages and pages of flat, boring, muddy washes and paintings. But with every painting I complete, I learn what not to do next time, which makes next time’s work marginally better – and so the inevitable loop of the infinite game rolls forward.

Even though my expectations will always exceed my capability, when I look back at my first work (just like looking back at my first job) I realise how far I’ve come – the things I’ve learned to avoid as well as the things I want to repeat. Making mistakes, after all, is just the process of figuring it out, whether that’s work, art, or life.