Whenever I start a project, expectations are high. I have a vision in my mind of what I’m aiming to produce and so I set out in search of that elusive goal – to make my hands produce what my mind can see.

The reality is that I almost never get there. In fact, if I ever have, it would mean I’d stop creating art. So, whilst in theory, I want to hit the goal, there’s something in the impossibility of the task that is the thing that forms my art practice.

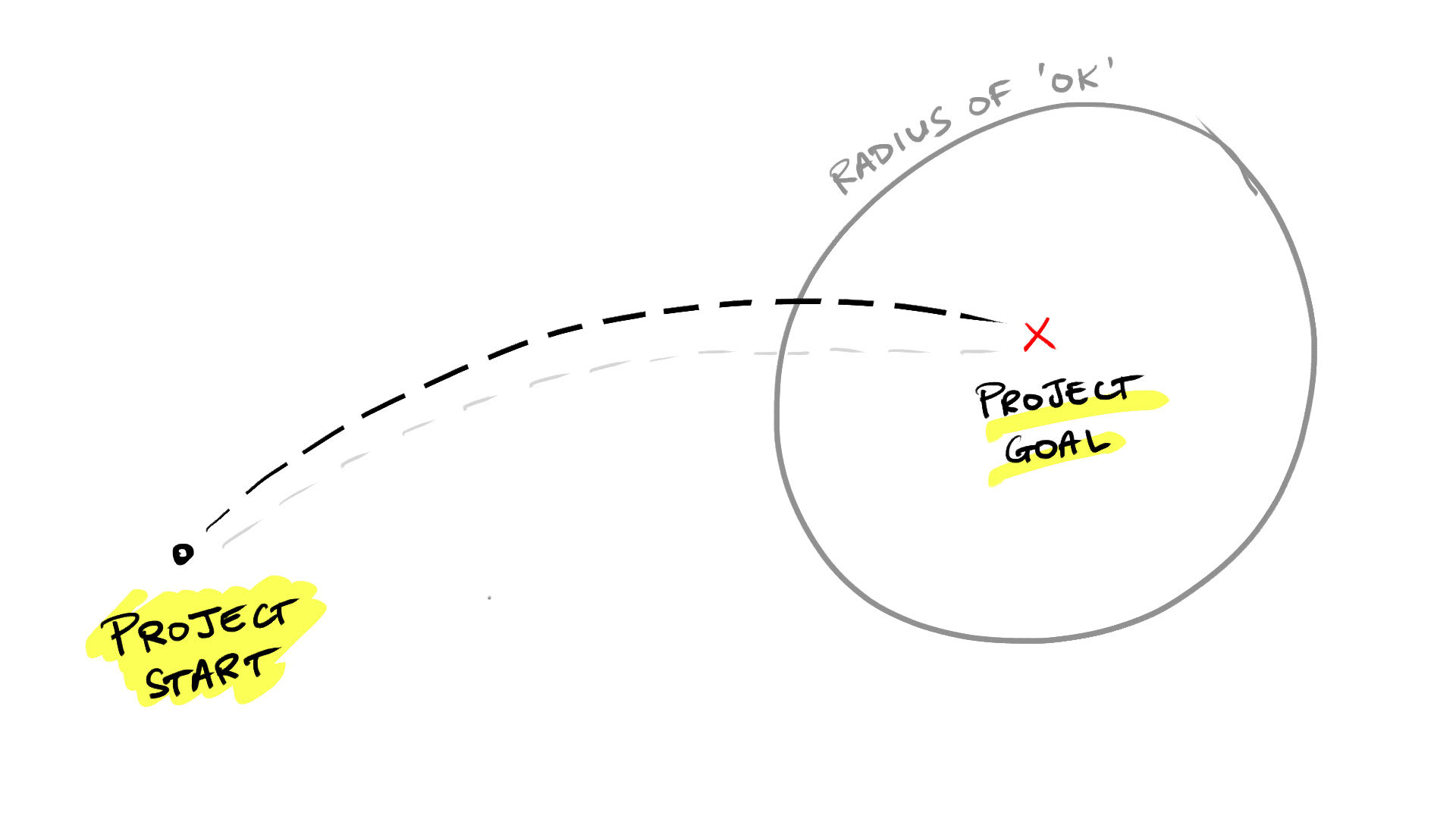

So, how do I publish non-perfect work? It takes practice. It takes an acknowledgement that, most of the time, the standards I set for myself are always higher than the standards that others set for me. That’s where the “radius of OK” comes in.

The radius of OK

The radius of “OK” is, in my mind, a ballpark. It allows me to ask the question – does this final illustration achieve what it was intended to achieve, even though it may not be exactly what I saw in my head? I don’t like to think about this as, you know, a percentage, or some imaginary bar to clear – that doesn’t feel particularly rewarding. It’s more about asking, “did I get close enough?”

Maybe it’s because I grew up playing golf, but, I know the chances of getting the ball in the hole from 180metres away is pretty unrealistic. But, hitting the green is something far more achievable. And, over time, the more one practices at golf, the better one gets at hitting the green. In golf, they have stat called “Greens in Regulation” which aims to capture this exact thing. Yes, getting the ball in the hole is important, but when you’re starting from a distance, hitting a green is just fine.