An art practice is a funny thing. We’d like to think there are rules, processes, or certain ways of doing things; things that are more likely to lead to success and/or failure. But, for every one bit of advice, there’s another contrary piece of equal value.

Take, for example, imposing constraints. I’ve written before about how I find constraints very useful. By imposing constraints, it can free us up to think and work within them. In a world of limitless art subjects, constraining ourselves can help us develop in a particular way. Or, like my studio space; it’s small. But it’s small size allows me to think cleverly about the space – to prioritise ruthlessly. It’s often priority that leads to progress.

Or is it?

On the weekend, I did something rare (for me) – I played with a new type of art material. I had previously constrained myself to watercolour. The theory was that the focus on just one medium meant I could push my ability to use it in ways that people before me had not.

But, in that pursuit for purity, I found myself in situations where I simply could not produce what my brain could I imagine. The frustration grew to the point where I dismantled the one constraint I’ve been living with for years.

In the process of learning about this new medium by playing around with it in my studio (I was painting swatches of the colours), I accidentally squeezed out too much green. So, instead of wasting it by letting it dry on the palette, I picked up a scrap bit of paper and painted a giant green swatch.

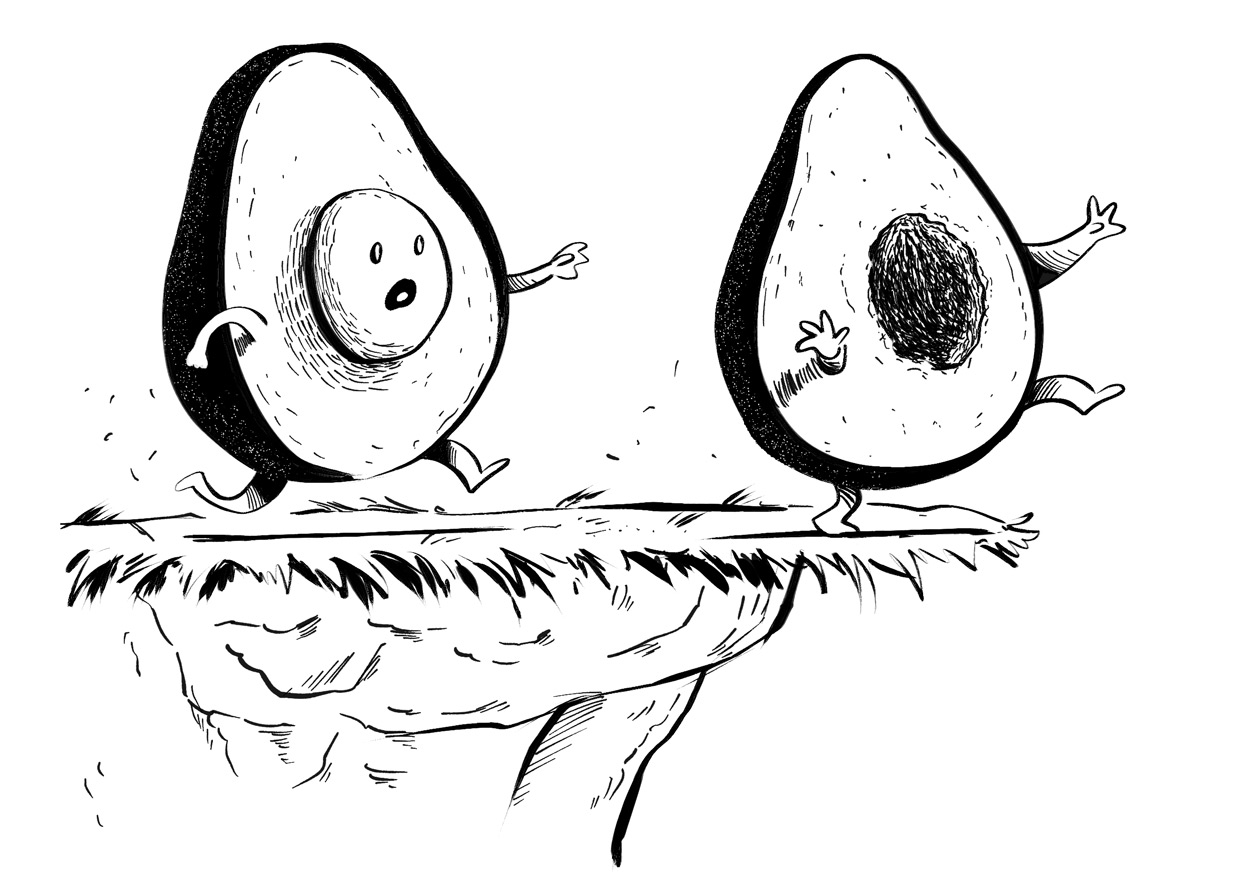

That giant (too bright) green swatch became a background for this image. In my mind, it was cute, but nothing exceptional (although I learned a lot about the new medium by painting this).

When I shared this image on Instagram in the last week, a publisher reached out – “Hey Matt, I think there’s a story here.”

There was?

And, sure enough, that prompt led to a new story idea which I’m developing as I write this journal entry. Will this story about an avocado be politically important? World-changing? A significant contribution to my body of work and my identity as an artist? Probably not. But, had I not decided to break one of the constraints imposed upon myself, that painting would never have happened. It’s an image I would never have produced had I constrained myself to watercolour.

Constraints are useful, but then, so is stepping outside of the boundaries we have sometimes to try something new. Like most things with art, there are not rights and wrongs, only what works. The act of art-making is, at its core, an act of discovering who we are and so, don’t we owe it to ourselves, sometimes, to break our own rules to meet a version of ourselves we haven’t met before?