What if illustration was a secondary career, not the primary one? What if you didn’t have to rely on drawing to put food on the table? What if, like me, the illustration work and the ‘day job’ could co-exist and, in fact, improve one another?

Golf, animation, design

When I was 16, I had to make a decision – to pursue professional golf (yes, I was a good golfer) or go to university and study something completely different. I chose the latter. Not from fear, but because I enjoyed the game of golf too much. I couldn’t imagine ever enjoying being in a position where a 3ft putt would decide whether I could eat that week. That sounded (and still sounds) terrifying.

My other interest was animation. In fact, I thought I wanted to be an animator. Pixar and Dreamworks were just hitting the stage at the time, so I picked a uni course that opened that possibility. But, I tried 3D animation for 3 weeks in the first semester and realised how it just wasn’t for me. Too fiddly, too technical, too… disconnected from the fluency of what drawing was for me, even though I didn’t really do it much in high school, anyway.

But, what I discovered at University was Design. Design as a practice. How it applied to architecture, objects, & software. That there were people and decisions behind the spaces we inhabit and the everyday tools we use. Before then, I never really thought about that, but since then, it’s almost all I’ve thought about.

I began a career in Design almost 20 years ago. I left the idea of drawing or animation behind in high school. I would be a designer. It blended the appreciation I had for aesthetics with the enjoyment I got from making tools for people.

I worked as a Designer for 15 years. Mostly making software products that paid (and continue to pay) surprisingly well. On the most part, I enjoyed the work but found myself burning out in front of screens (I was staring at a lot of them, most of the day).

As an escape, I picked up a pencil and piece of paper for the first time in 15 years, and just drew things. For me. It was meditative, imaginative, and it re-ignited the storyteller spark in me. Because of my Design career I had enough money to buy nice materials and try many different things.

And then, a funny thing happened – I was ‘discovered’ on Instagram and offered an illustration project; in fact, 3 books… at once.

It doesn’t have to be a binary choice

Now, 8 years after that moment, I’ve got 20+ books in market and a continuing career in Design. They work together and activate different parts of my complex self. I hear illustrators who say, ‘but I can’t do anything else but draw.’ I wonder what the chances really are of that, given humans are such complex beings. Perhaps those illustrators are just more afraid of ‘letting illustration go’. As if you either are or aren’t an illustrator. But, it’s not a binary choice. It can be an ‘and’ not just an or. I’m living proof of it.

For me, the Design work I do activates the logical, deductive, and scientfic part of my brain. It forces me into situations with people that, left to my own devices, I’d probably normally avoid. But, the flipside of being in these uncomfortable situations is that I’m gaining different perspectives on how others go through the world – that’s critical to evolving my picture book work.

The illustration work I do activates the inner introvert in me – it is quiet, meditative, and isolating. The interesting thing about this mix of Design and Illustration is that they both share the most fun bit – lateral thinking and imagination. Once I’m exhausted from collaborating with others in Design work, I get to spend time alone drawing things.

Design and Illustration also work together to help me manage financial goals. I don’t need to illustrate a book to put food on the table, which means I can pick and choose the illustration projects that appeal to me emotionally. I know that, because of this, I also produce better and more authentic work, which, once again, feeds itself with more projects I like to do because it’s the authenticity that sells.

I can’t imagine how much pressure one would be under to make illustration the primary income stream, not just for oneself, but also supporting a family. It changes everything.

If it’s your primary income source, then when things are lean you may need to draw things you don’t feel like drawing which, in turn, creates illustration that you may not be authentically proud of. But, what inevitably happens is the work you do is the work you get so those illustrations become your body of work and people then believe ‘that’s the work you do’, so they ask you to do more of it. Unless you’ve got personal projects on the side to help direct a folio towards somewhere you want it to go (which is just extra, unpaid work anyway), you end up cornered.

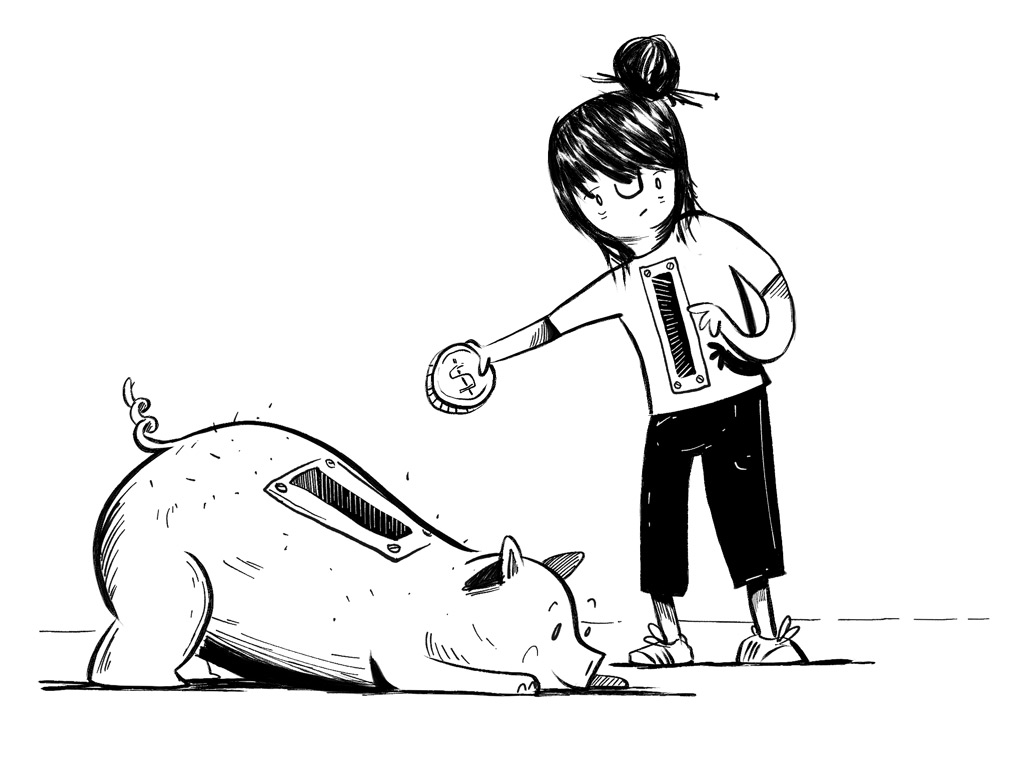

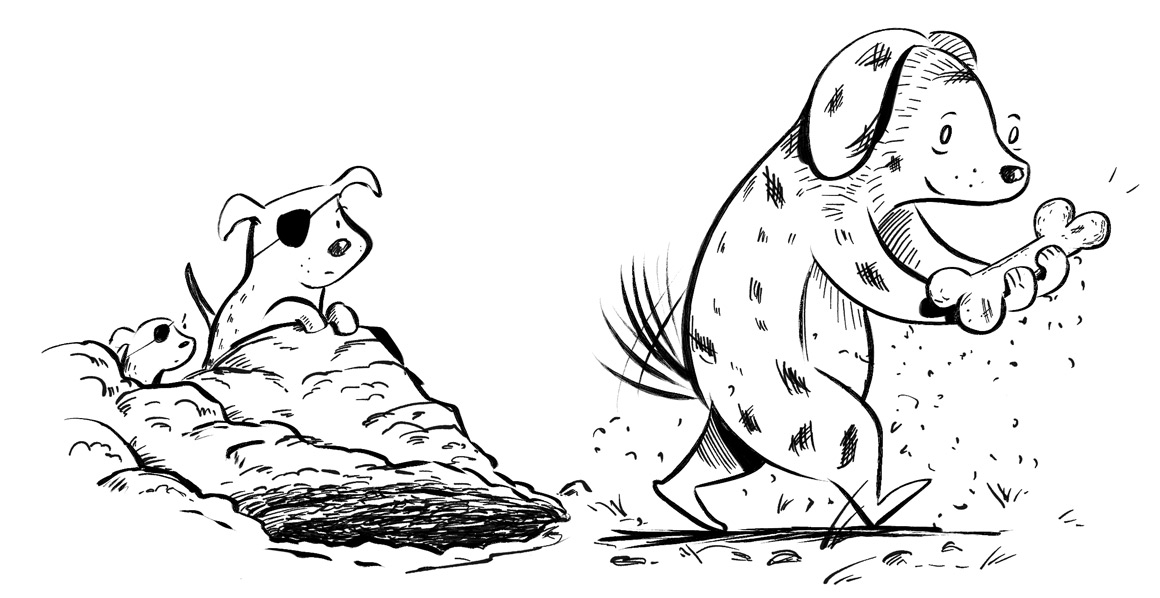

From a financial perspective, the way people buy illustration is incompatible with the way bills come in. Bills are regular – like waves at the ocean. Project-based income is not; it’s lumpy. There are some periods of abundance and periods of scarcity. One might say, “save some of the abundance for times of scarcity, like a squirrel stores nuts”, but, with illustration, there’s no guarantee that another nut is coming at all. Or, at the very least, it’s not in the illustrators control, no matter how much ‘marketing’ or ‘self-promotion’ you’re able to do. That sounds incredibly stressful.

I’ve experienced freedom by committing to illustration work as a secondary income stream, and along with finding a primary one that doesn’t drain my creative energy, I’ve found it’s possible to have both. Maybe there are others out there who may find the same thing?