I’ve been thinking about this copyright versus open-source thing for a while. Is it better to offer ideas for free; a gift to the commons? Or is it better to protect your ideas and demand payment for their use and/or replication; what’s mine is mine until you pay enough.

For years, I’ve erred on the side of the latter, afraid to upset an industry like publishing and the people who work so hard at protecting ideas so that artists can make a living. But my heart (and my experience in the software world) is telling me that gifting the commons may simply be better in the long run.

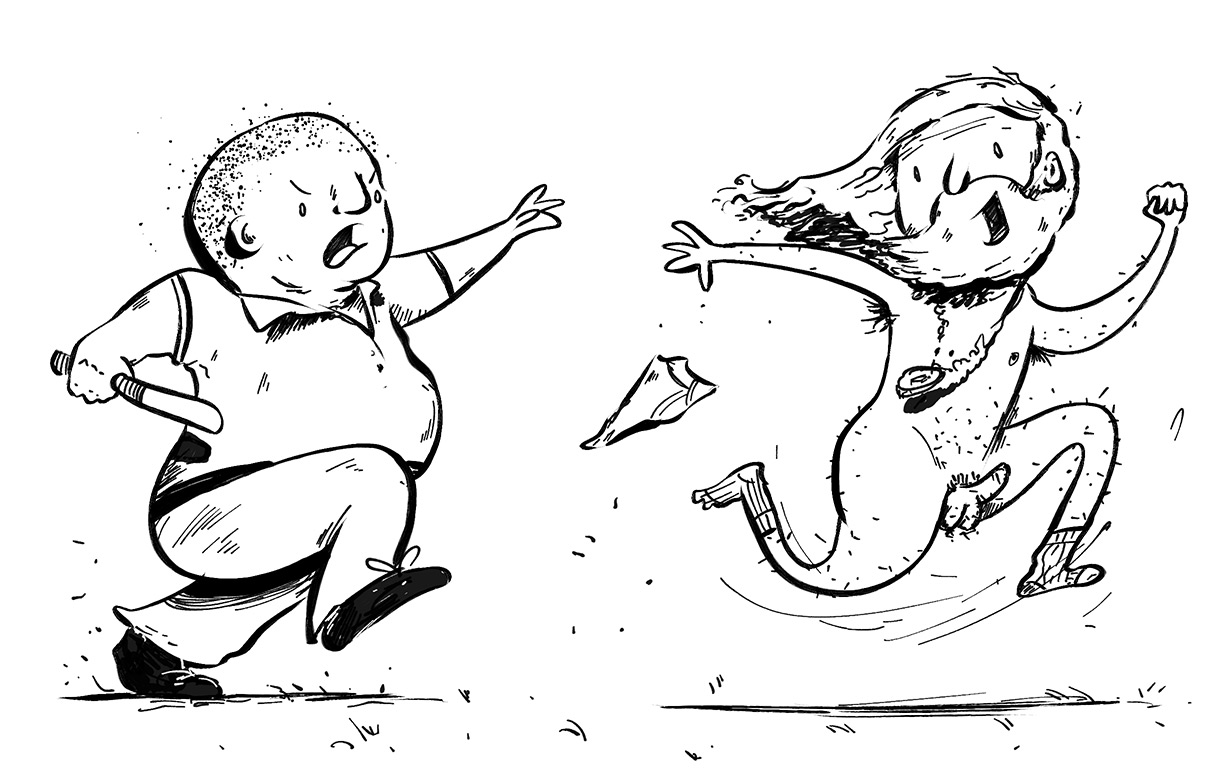

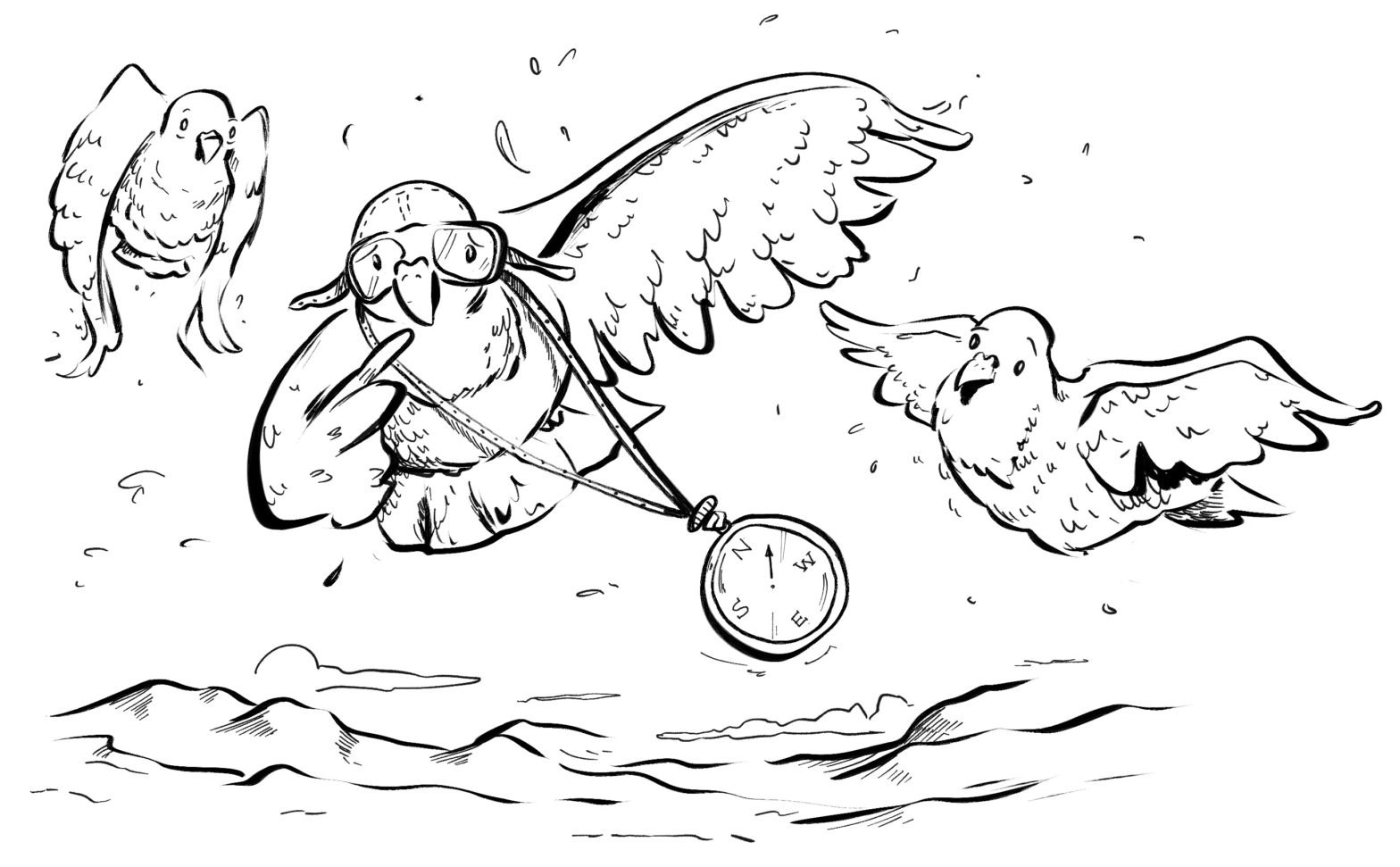

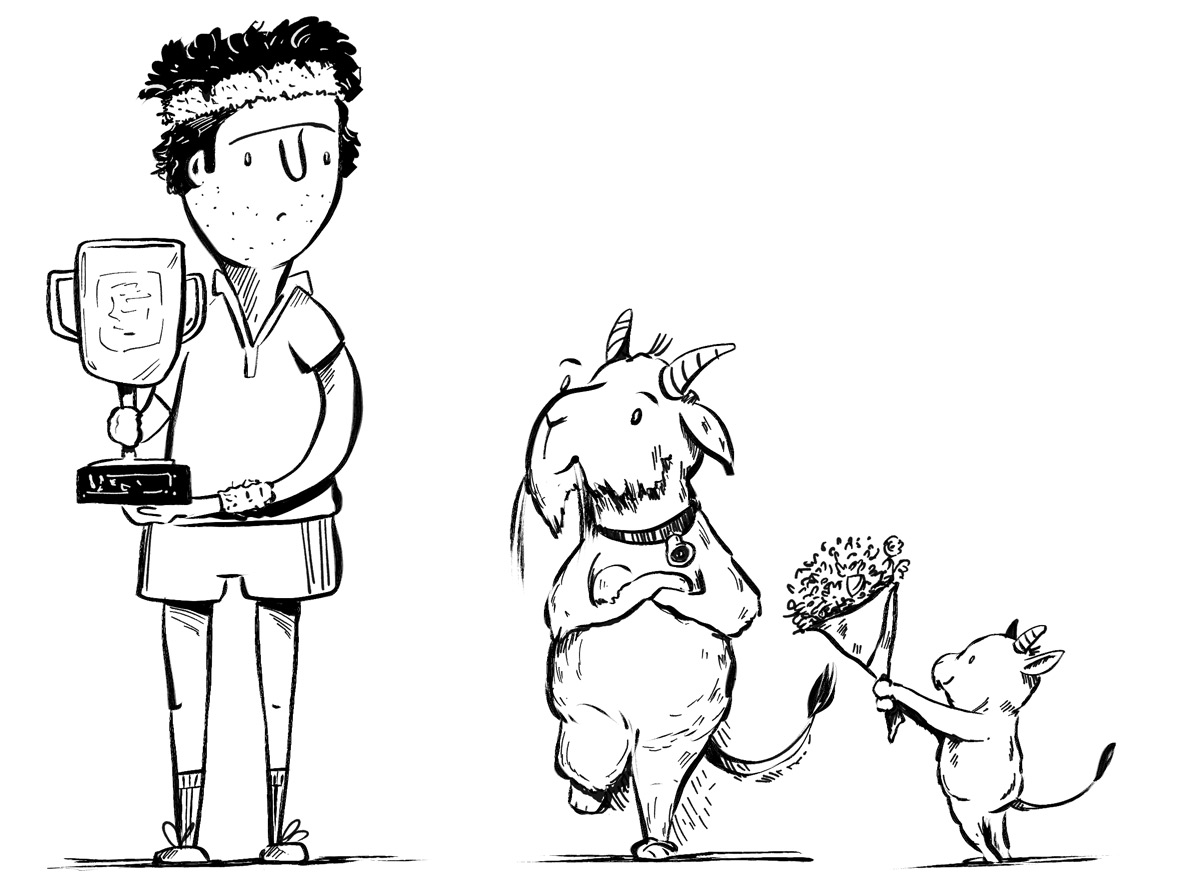

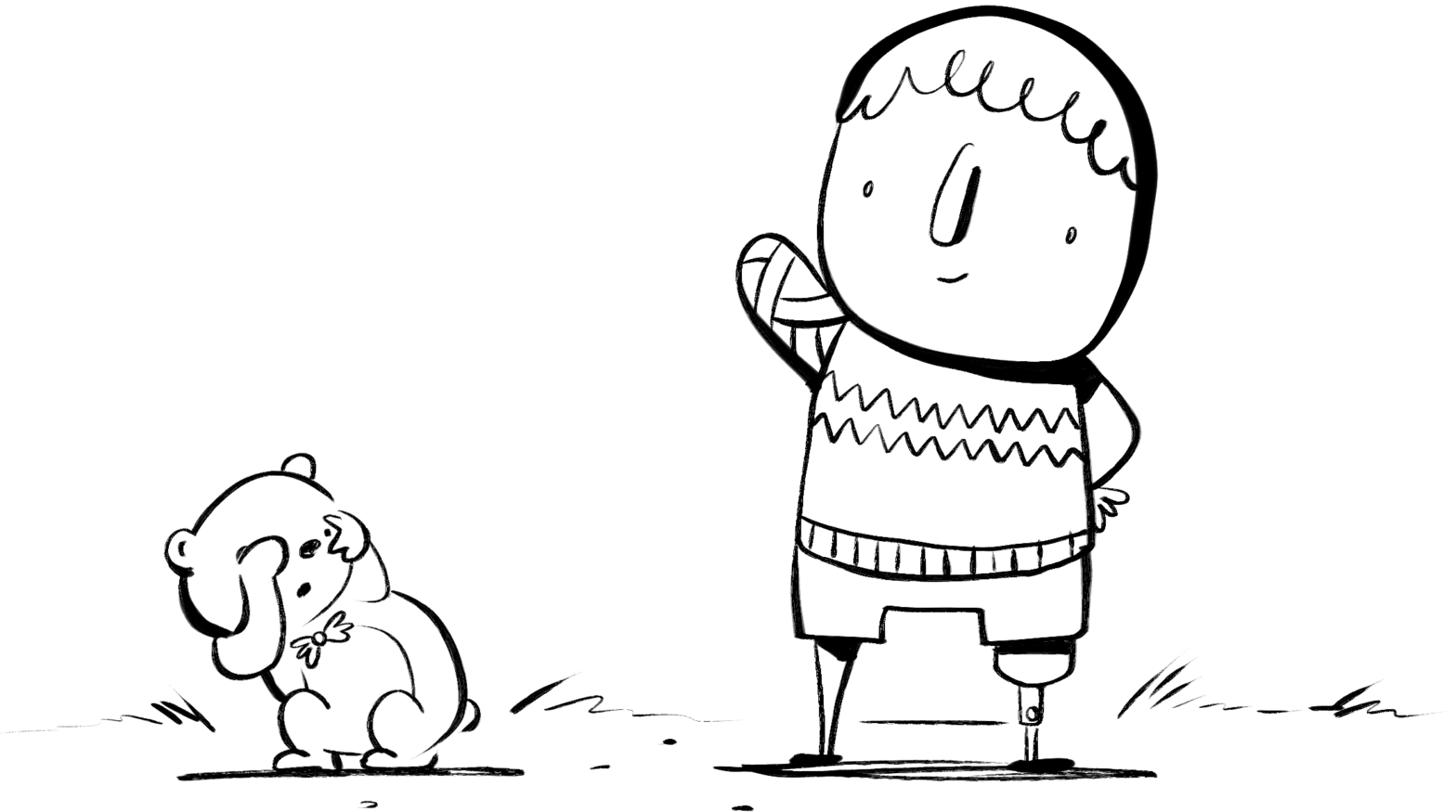

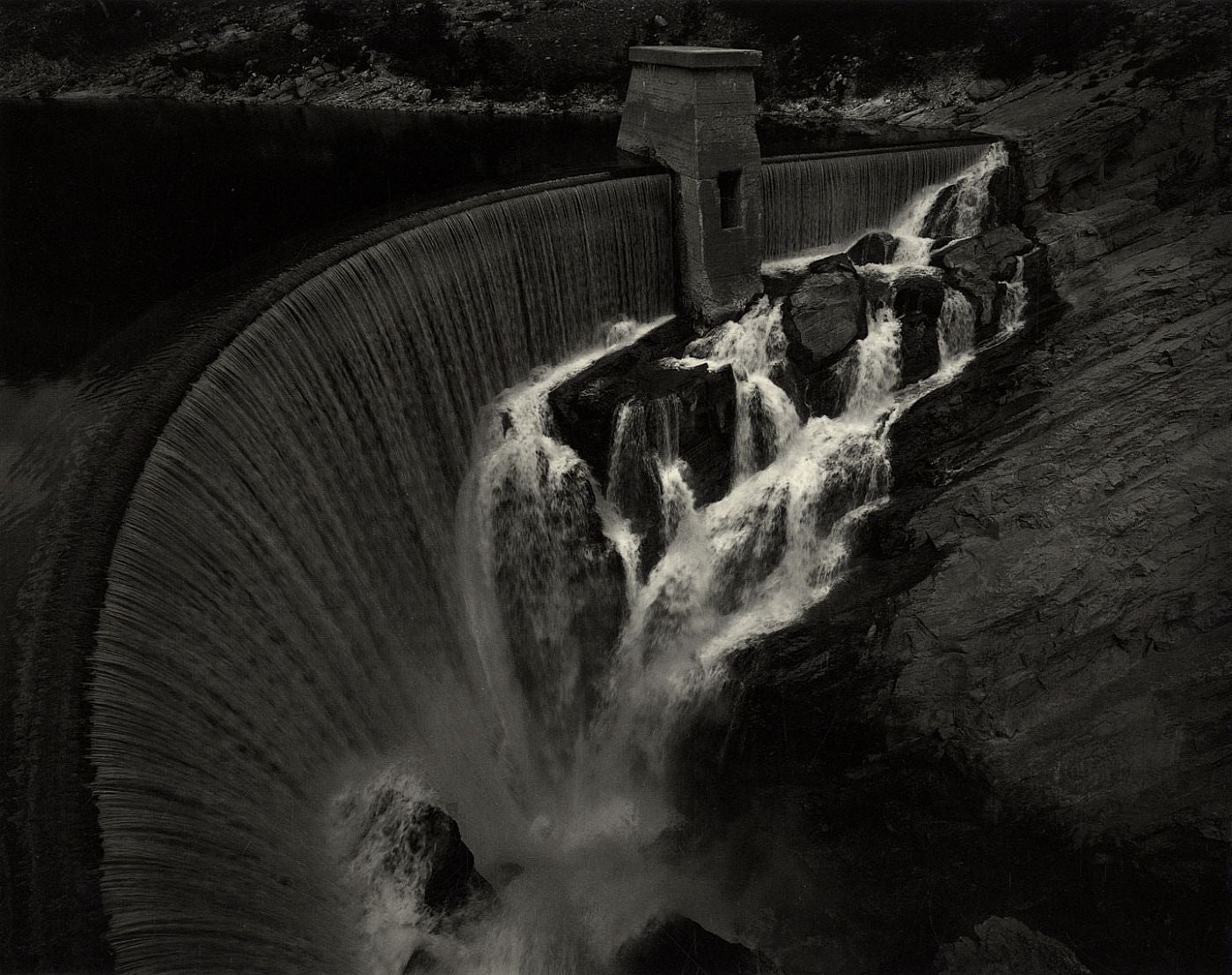

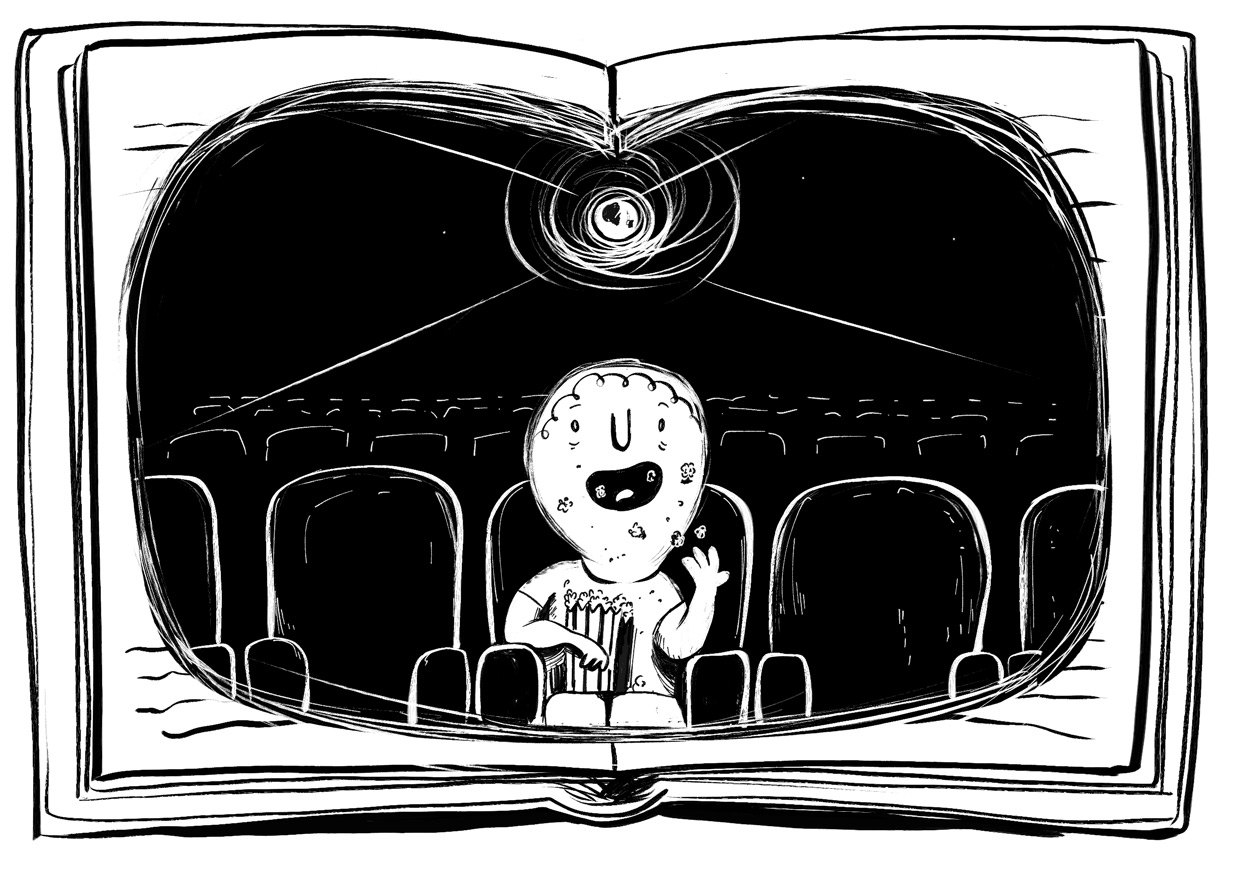

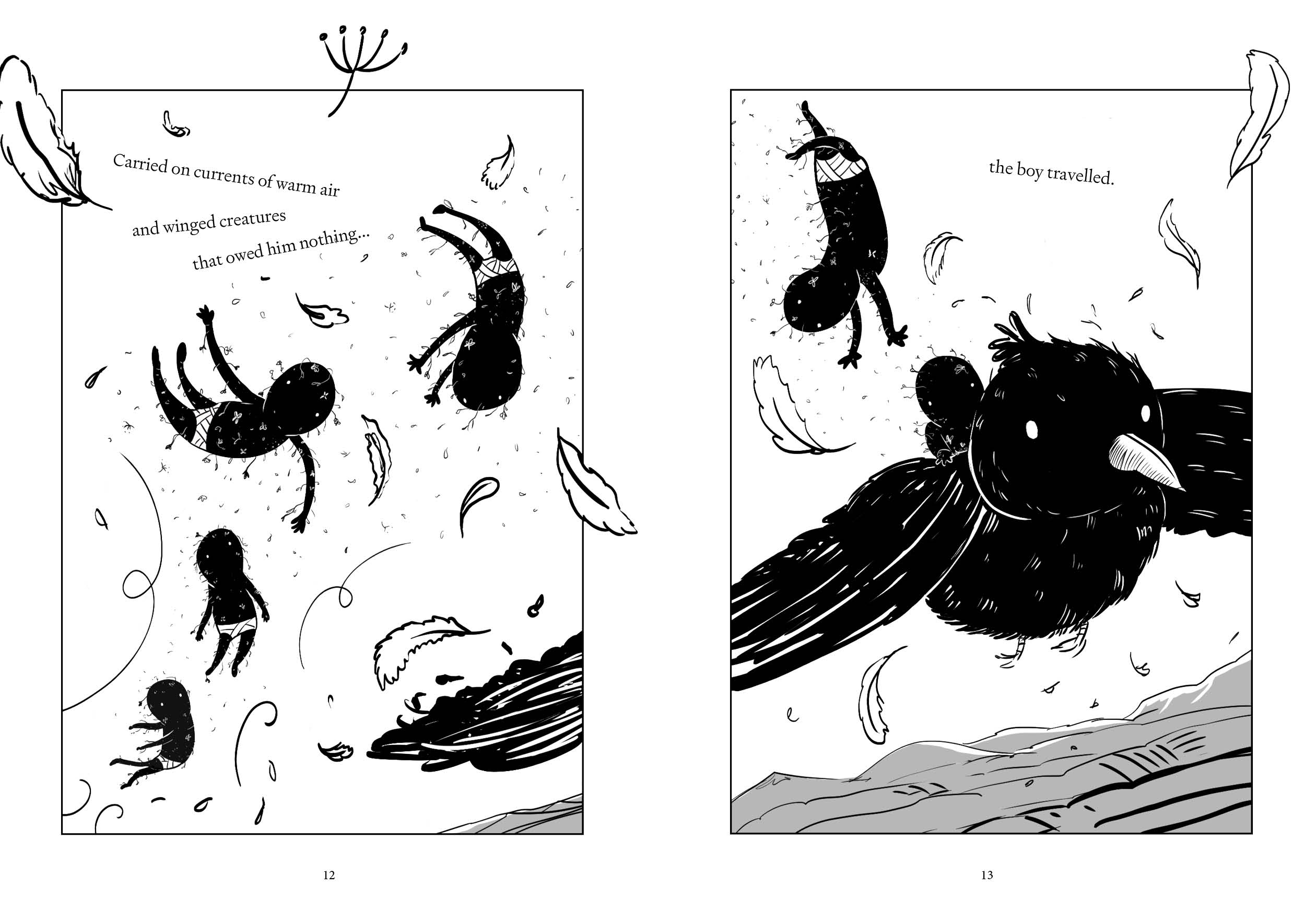

This week, I finally followed my heart and released This Generous Earth. It’s a gently philosophical graphic short story about the human story of separation from nature and how we might re-think that story in order to live more meaningful lives.

I guess you could call this self-published, but it’s far less structured than what the marketing boffins would advise you to do. I didn’t use some flashy and strategic marketing campaign, I just put it out there, “Here, I made this. I like it. I hope you do, too.”

I sweated for a days on how I should price it. $10AU? $6AU? $4AU? I flip-flopped between “I value my work so others should too” and “But what if you can’t afford to read this but it’s an idea that unlocks something in someone.”

So, I’ve taken one step down a path of my love of free ideas – pay what you can. Suggesting a price lets others know I value my work at some monetary level, but it removes any of the barriers of access that emerge from socio-economic disadvantage. As I’ve written before, the biggest threat to the arts isn’t piracy, it’s obscurity.

I’ve always trusted that if people had the money, they would pay for creative work. Now, I’m putting my money where my mouth is. This Generous Earth took me almost 100 hours to complete. And, I know it ain’t going to win awards or top best seller lists. But, it’s a story and form I love, and so I’m trusting that others will love it, too.

Releasing This Generous Earth has also had one unexpected consequence – it released me from it’s grip. It’s changed my primary question from, “What will I do with this story?” to “What’s next?” And that’s more liberating and exciting than any best seller list has ever been.