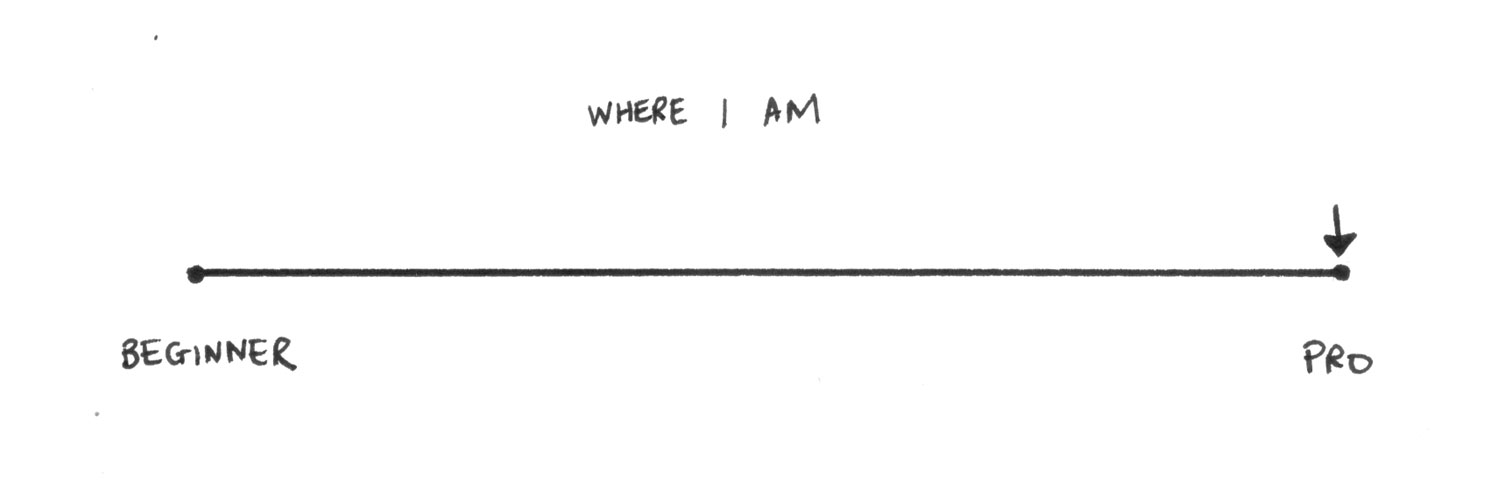

There are many things I consider when I’m deciding whether to put an idea out into the world at scale through a publisher. It doesn’t matter whether it’s text I’ve written and illustrated myself or a text I’ve received from an author where I play the role of an illustrator; I don’t think there’s a more important question than, “Is this idea really worth spreading?”

Valuing an idea is difficult. Balancing the ideological and behavioural impact of my work against its economic and environmental impact is a bit like comparing apples and oranges.

What’s the cost of an idea?

Any idea, published at scale through a publisher takes resources. Trees have to be cut down, that’s a given. But the chemicals used in the inks need to be manufactured, the book likely needs glue for the binding. If it’s a gloss cover or if it has some unique finish, there’s likely to be polymer and plastics involved; things that will never degrade.

There’s the creation of the artwork, too. Oil paints (petrochemicals), acrylics (plastic), watercolours (pigments like Cadmium), the paper or canvases needed to create the work, the brushes manufactured from natural and synthetic hairs, the wood used to make the brush handle, the list goes on.

Oh, and don’t forget the labour. Publishing a book means that actual humans are spending their finite time on Earth, helping to spread the idea. Everyone from the publishing team, sales and marketing, and the book printers and suppliers. The people who drive the delivery trucks and planes to the bookstores across the country, maybe even across the world, and of course, booksellers. It’s all part and parcel of bringing what most people see as a ‘pretty simple book’ to market.

Maybe I’m thinking too hard about this, but it costs us humans a lot to spread our ideas in this way.

What’s the impact of Queen Celine?

The irony of writing, illustrating, and publishing a book about the impact of our actions on the environment (like Queen Celine) is not lost on me.

I genuinely believe that the printed word, bound in books, is one of the most potent behaviour-change tools humans have ever invented. There’s no argument that the speed and convenience afforded by the simple printing press changed humanity forever. The format of the book is archival. It can last hundreds and sometimes thousands of years as long as it can escape its nemesis, fire. It’s been our primary method of intergenerational knowledge transfer for centuries.

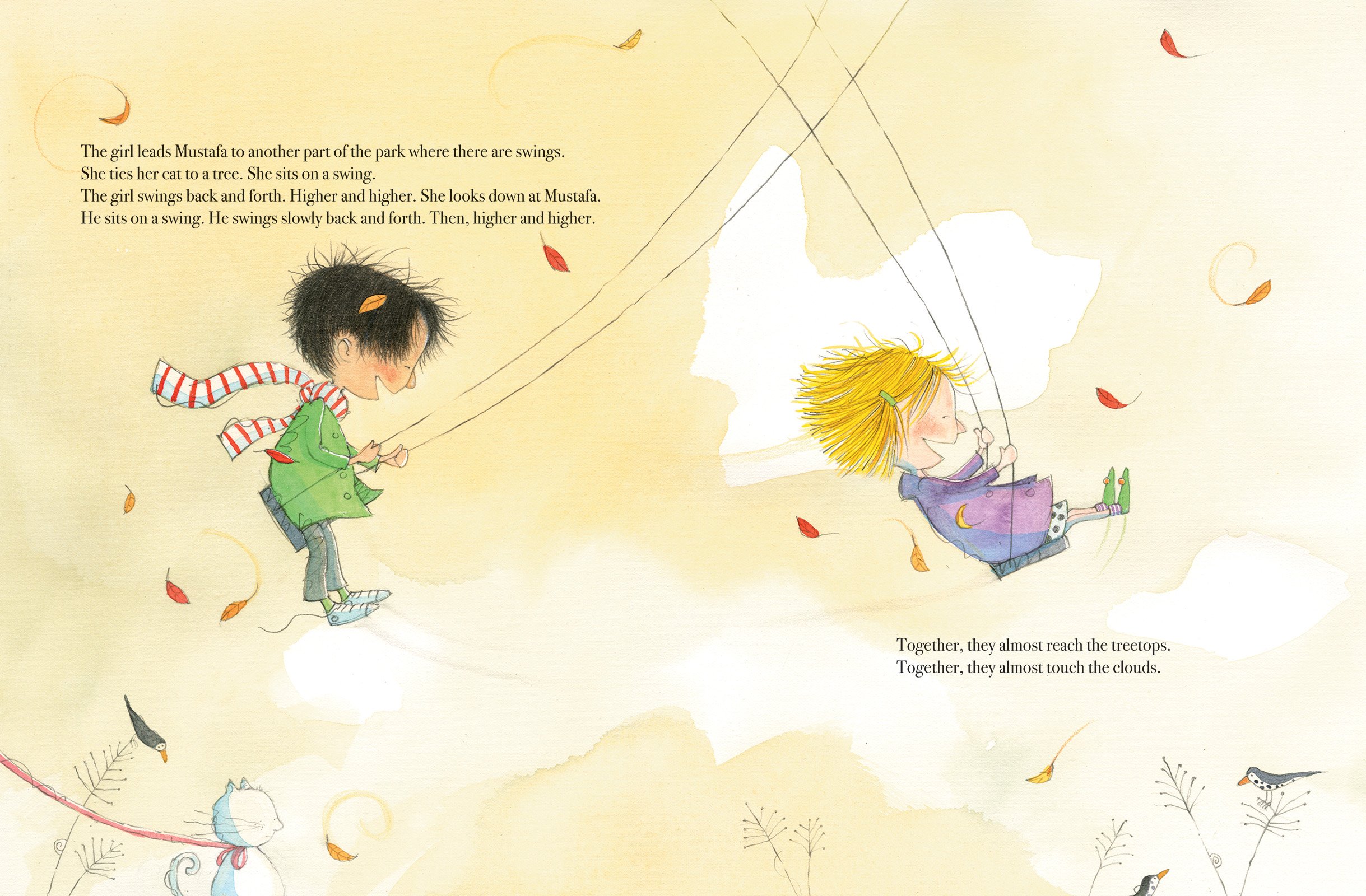

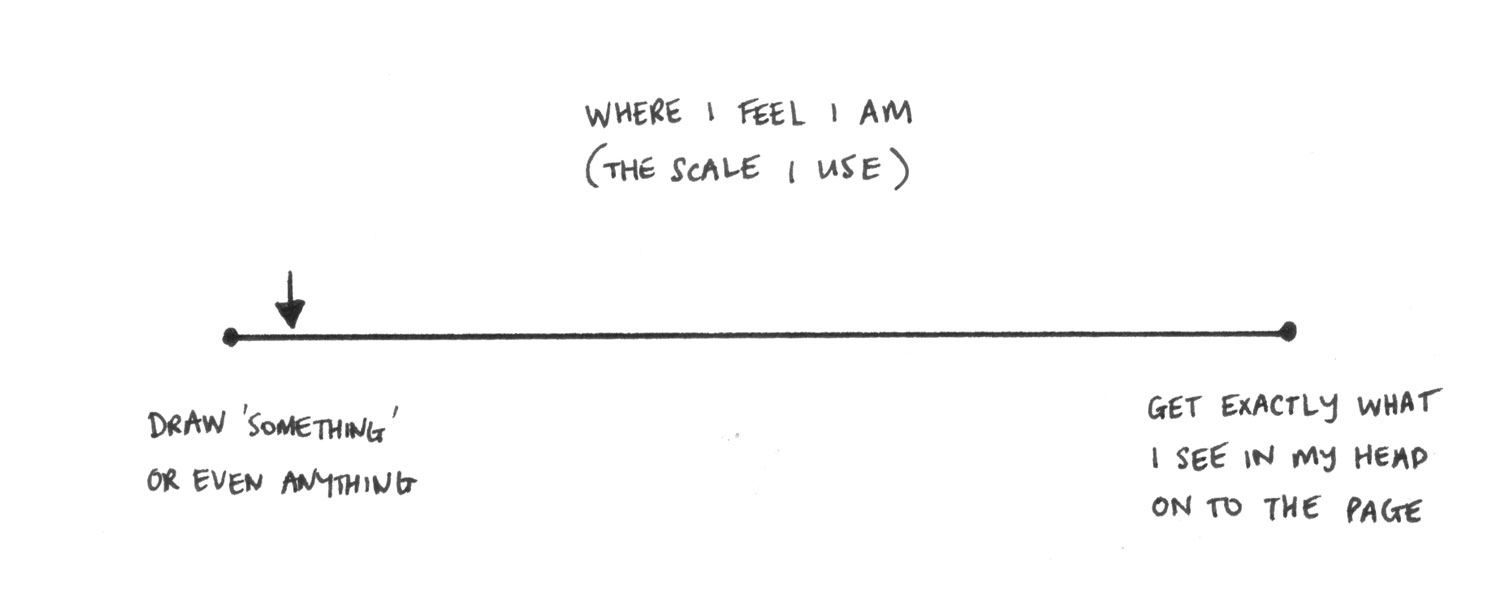

To make me feel OK about using precious resources for spreading my idea, I work SO hard to make sure that a book like Queen Celine has the best chance of making the change that I seek to make. And no, that’s not to accumulate awards or make me enough money to be a full-time writer. And it’s certainly not for my ego. What I want from any of my books is to introduce a different perspective to someone. Make them think a little differently than before. Open their hearts and minds to the experience of others. If they can think differently, maybe they’ll act differently, too. Or, at the very least, with a bit more empathy. Perhaps they’ll be more kind, more forgiving, more understanding. The things that I think the world needs right now. I sweat obsessively over every word in the book, every punctuation mark, every line I draw or colour I select. Every single thing matters because it’s a terrible use of resources if the book doesn’t achieve its purpose.

Whose choice is it, really?

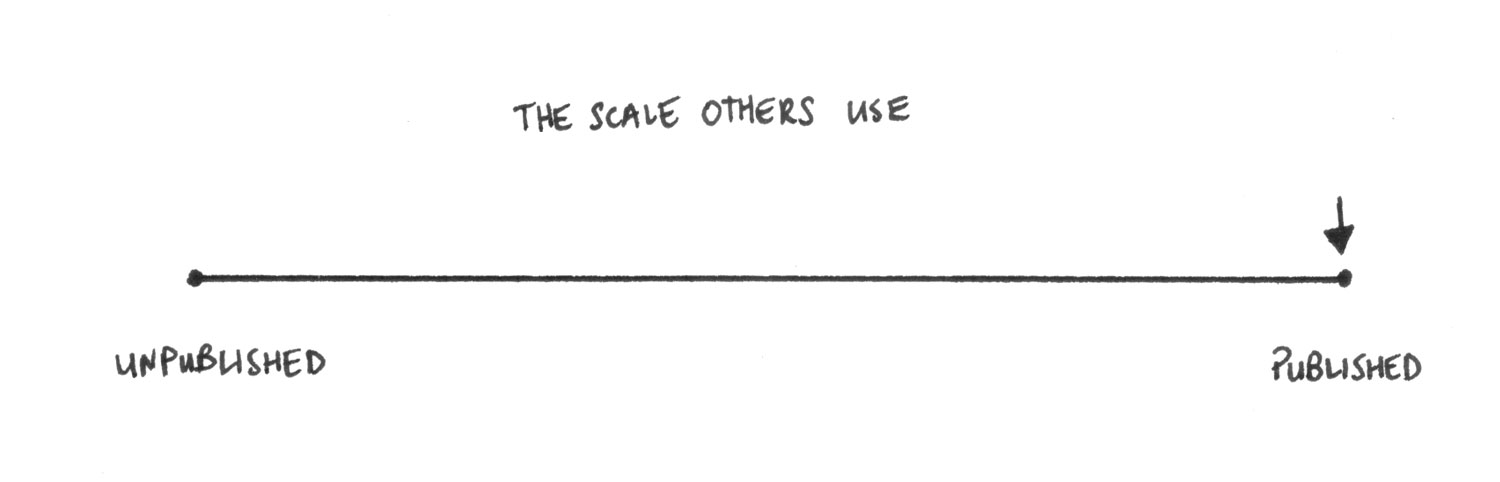

You might say, “Gee, Matt, you’re taking getting published for granted a bit, aren’t you?” And you’re right, I am. But although publishers are gatekeepers of sorts, what concerns me, I suppose, is that I don’t hear the industry talking about whether an idea should have the world’s meagre resources used to spread that idea in the physical form. I know publishers talk about “Return on Investment”, but it’s often regarding the simple, financial equation of “How much money did we pay the printer and author? How many copies did we sell? Did we end up in the black or the red?” And I don’t judge that approach either. It’s necessary so that publishers survive so that books do.

The generous optimist in me would like to assume that the selection criteria used by publishers have the “What is the strain on the Earth’s resources” question implicit in them. But I haven’t seen evidence of this so far. I’ve had plenty of ideas turned down, but I haven’t had a book turned down because, “We don’t think your idea is worth the irreversible damage to the planet, sorry.” For what it’s worth, I would love that! The reasons I hear more often are “The market for this book isn’t clear or big enough” or “Sorry, this isn’t something that fits with the rest of our list right now.” It suggests that a focus on financial ROI and reputation or brand is at the core of the decision-making process.

So, if publishers aren’t judging an idea against its impact on the planet, maybe it’s up to authors after all? Maybe it’s in our court to objectively assess our ideas and really try to understand whether this idea that we’ve had – this bright spark of inspiration – is worth spreading in the resource-intensive, traditional format of a book. Do we need another book about poo? Do we need another book about the alphabet? And if we do, then why? What’s so special about this idea? How will this change lives in a different way than what’s come before? If this idea was spread and the plastic cover it was printed on never degraded, would it have been worth it? Maybe if we use criteria like these on ourselves before we seek an agent or a publisher, we’ll only take our best ideas – truly life-changing ideas – to them. Maybe it’ll reduce the disappointment we get when we receive hundreds of rejections and it’ll increase our chance of being published anyway because we deeply, truly believe that this one is worth it — win-win.