One of my favourite reent quotes from Seth Godin is “If you want to ride a bike, don’t watch a video, don’t read a book.” There are just some things that you can only learn by doing, over and over again.

When I was a kid, I loved comic strips. Our school library had a lot of Garfield and Snoopy and I remember spending many hours there poring over the drawings, watching how the writing and the panels interacted with one another to produce yet another brilliant punchline. Of course, as a kid, I didn’t know that’s what I was doing, but as an adult it seems so obvious now.

Like with many young people who had an interest in art at primary school, when the ‘reality of the world’ began to take hold in high-school, I made choices that would set me up ‘to get a job’ and not ones that involved any sort of art-making. I never really returned to comics (or art) for about 15 years. You might think, ‘Oh, what a shame’ but there’s a silver lining to all things.

Re-discovering comics

I’m not sure when or how it happened, but I’ve been re-kindling my buried love of comics over the last few years. I unashamedly love reading them and I think the shame often associated with it has something to do with how we preference text literacy over visual literacy from a very young age. I’ve got a growing comics collection, including my treasured set of Calvin and Hobbes, and I’m slowly understanding my preferences for genre and subject matter (as well as artists like M.Sassy.K one of the colourists from Isola).

But, I’ve never made a comic, not one. I’ve read books on how to make them – most famously, one I had since childhood, but also Understanding and Making Comics by Scott Mccloud. I’ve watched videos on them, too, and there are some lovely resources online to help one get their head around what’s involved in making comics. But, as Seth Godin says, “If you want to make comics, don’t watch a video, don’t read a book.” I know the theory: good characters, panel arrangement, layouts, colour palettes, joke writing and pacing, the art of lettering etc. I’ve studied it all, but there’s nothing as helpful as, like I say a lot, just doing the work.

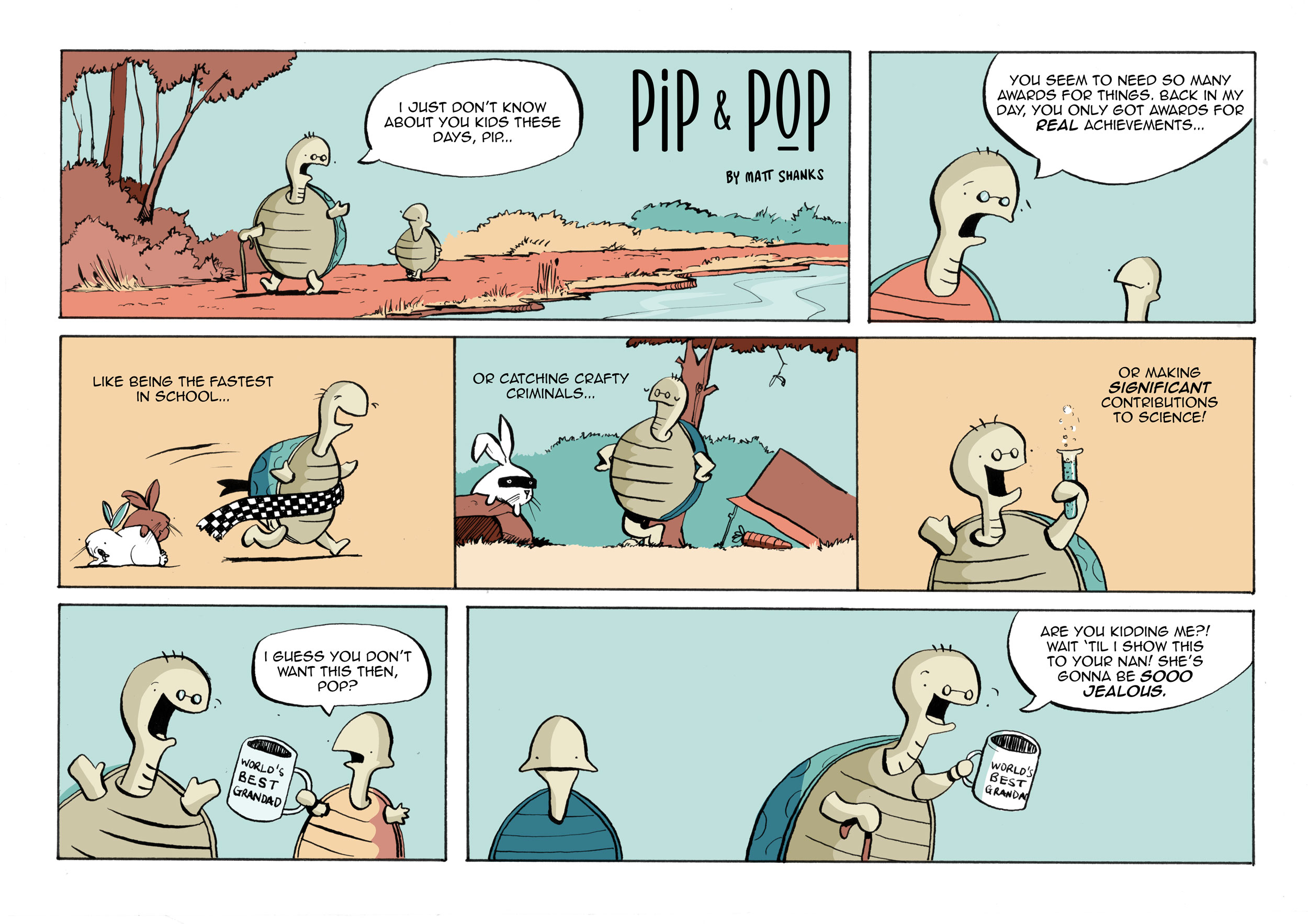

Meet Pip and Pop

If there’s one thing I’ve learned about true art-making is that its purpose is to help me answer questions. In Queen Celine, I was trying to understand what I thought of change, good leadership, and bio-diversity. In Eric The Postie, it was about exploring tenacity when even in the face of lost opportunity, if you think creatively it’s possible to find a way through.

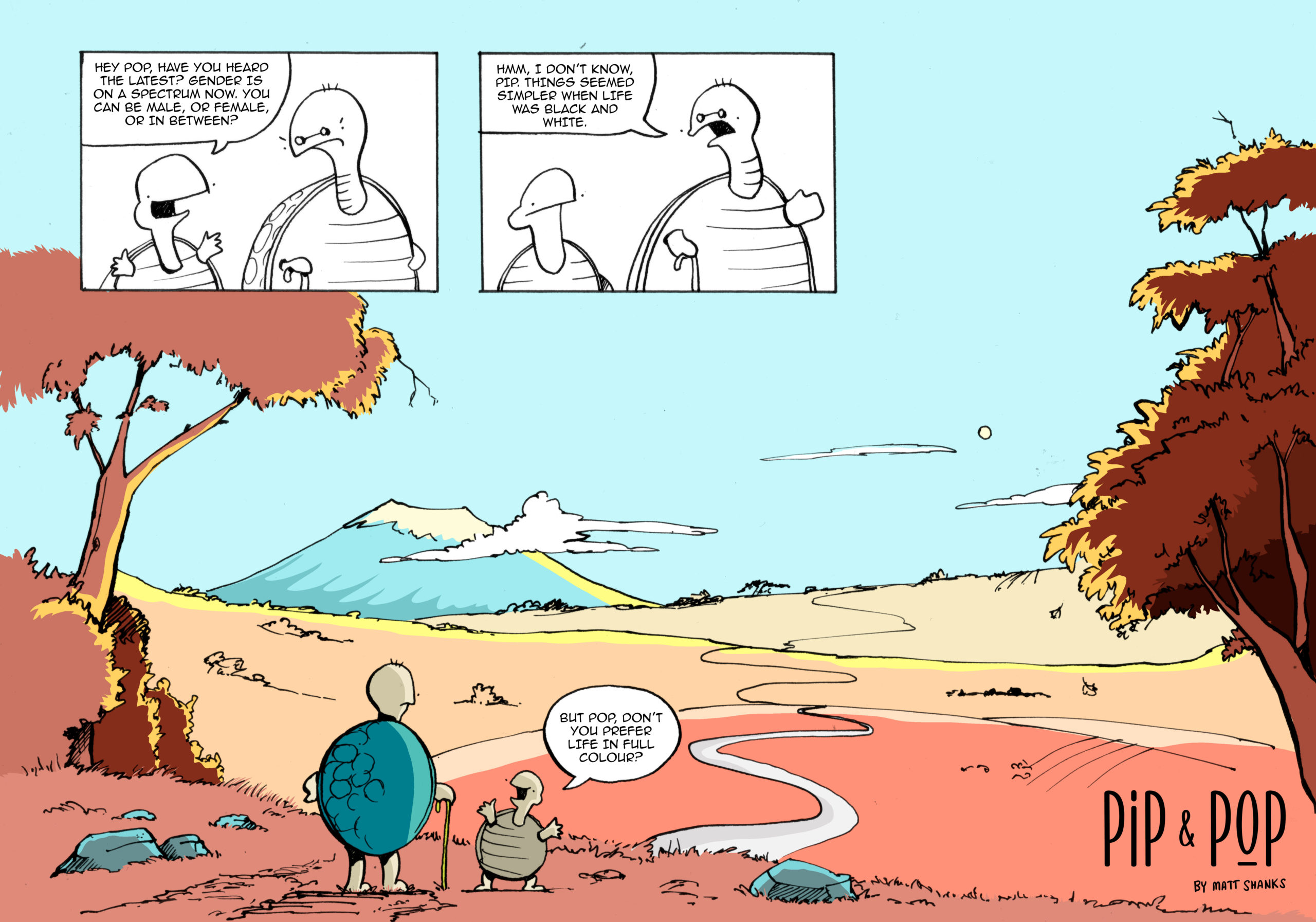

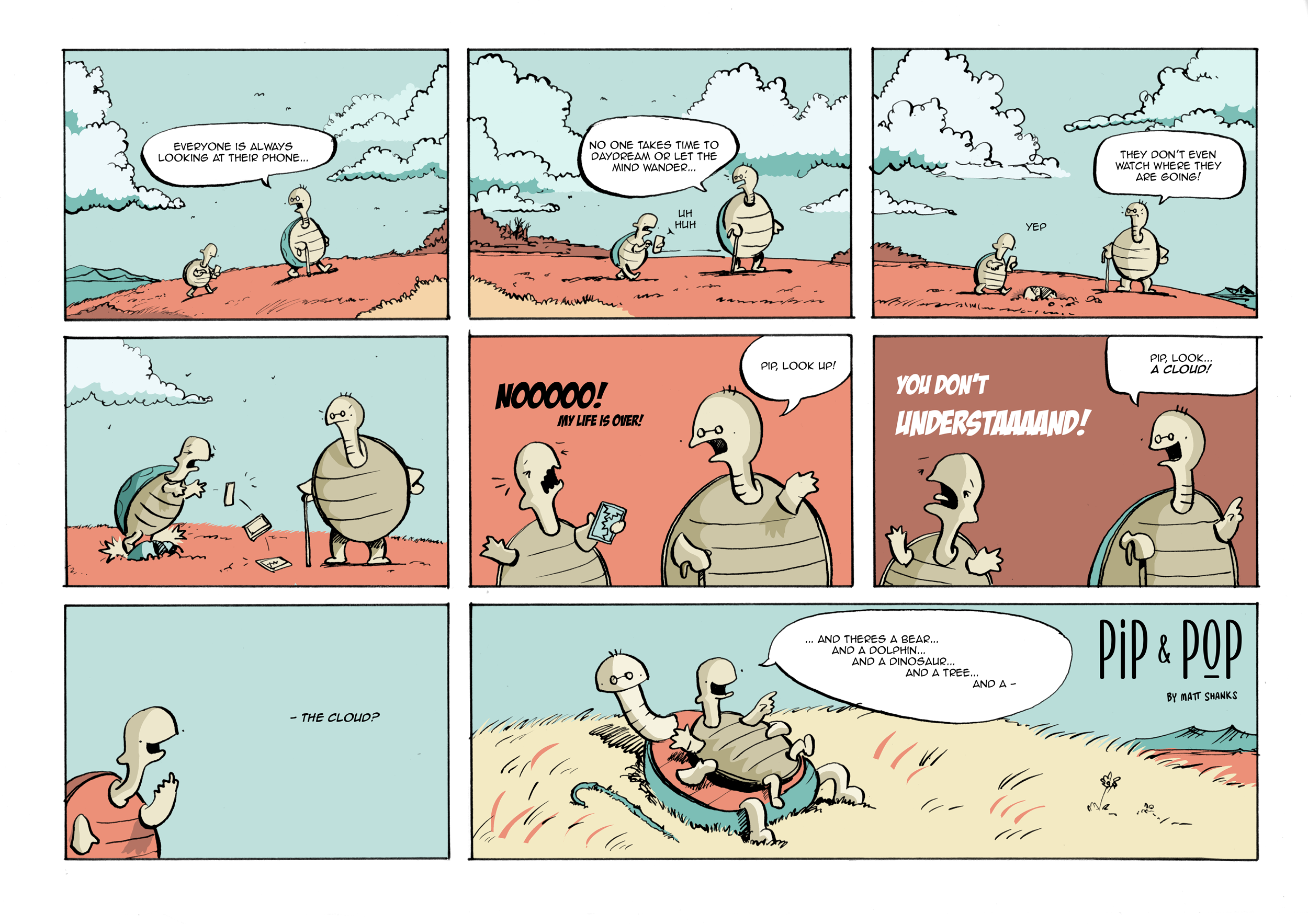

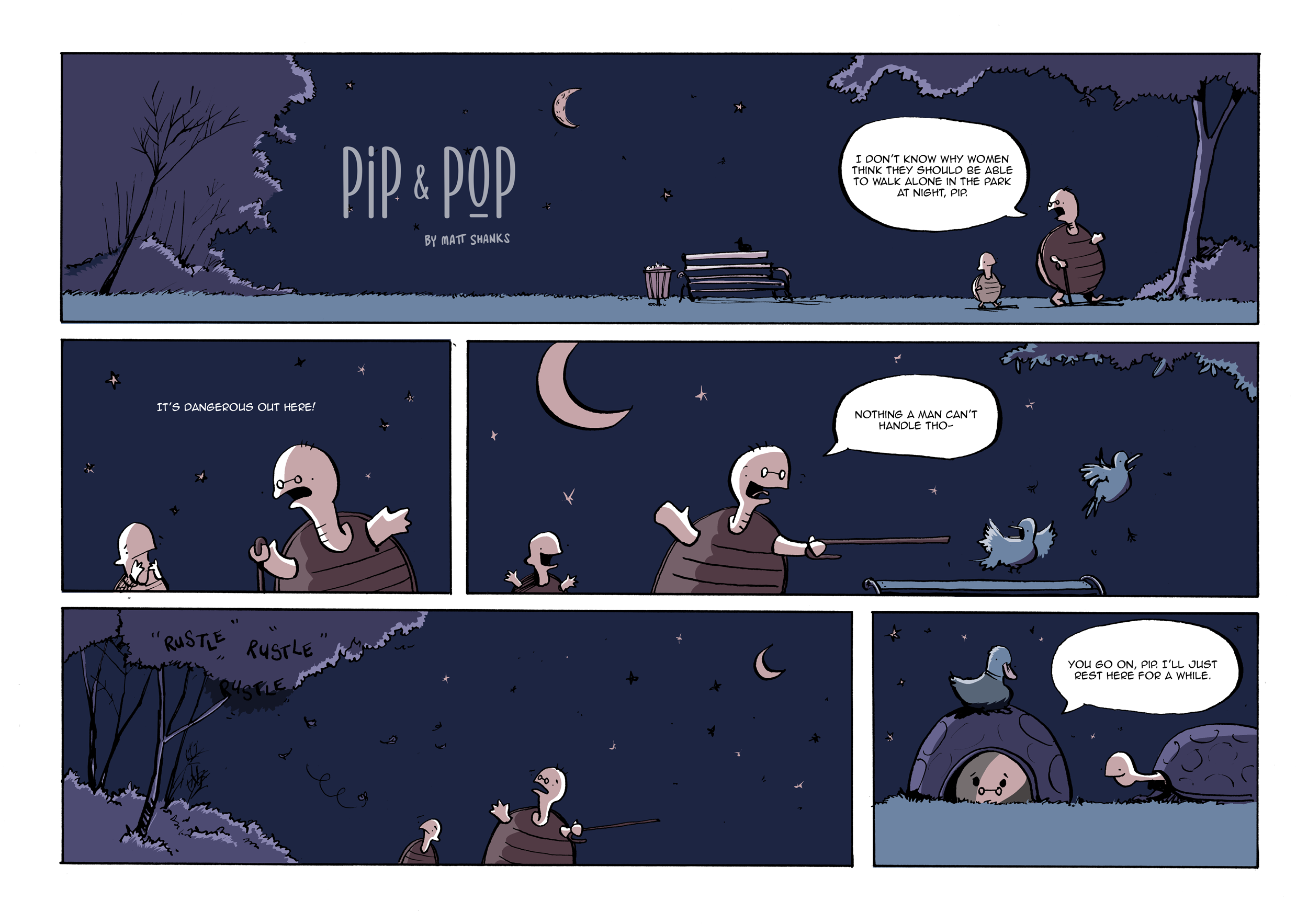

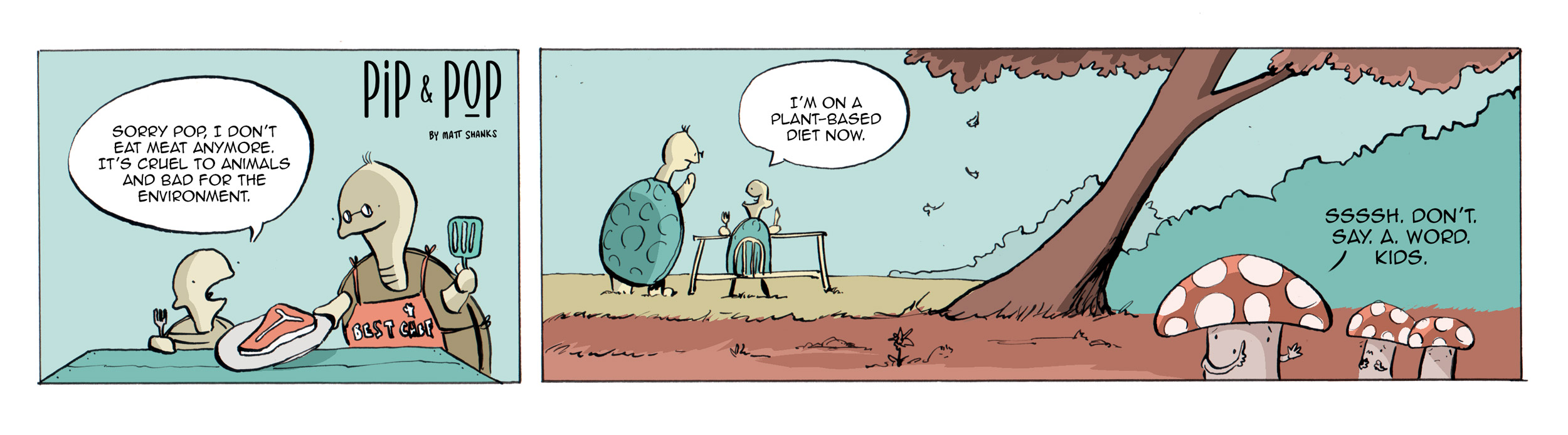

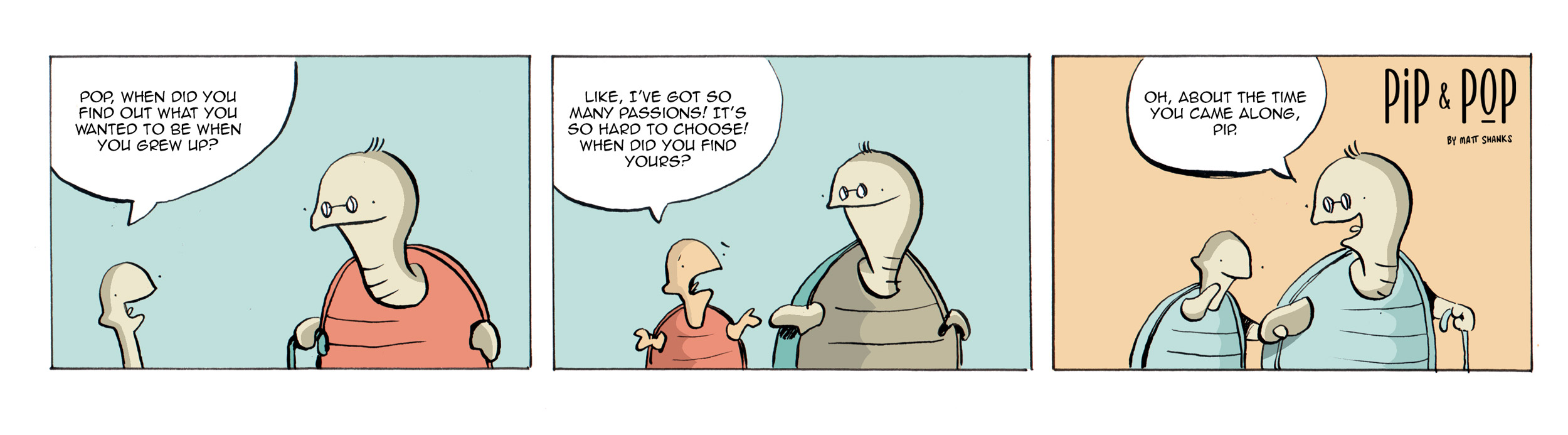

A question that’s been bubbling away in my brain for a while has been the one about intergenerational conflict. Seeing the rise of phrases like “Ok, Boomer” have been deeply worrying to me because it shows that we’re inventing ways of closing conversations, not opening them. Pip and Pop gave me a way to explore this. They’ve taught me that each generation has something to learn from one another. We’re all imperfect, and we’re all just doing our best. No one is truly right or wrong, there is no right or wrong, and to be honest, in the cosmic scheme of things, a lot of it is humourous.

So, who’s Pip? Pip is a young’un. He’s living in a fast-paced, connected world – part of a global community. He’s a ‘digital native’ – part of a generation that has never known a world without the internet. Pop, on the other hand, Pip’s grandad, remembers simpler times. Times when nature was the primary entertainment. Times before the internet where one read the local paper, engaged with the local community, worked hard, built a life step-by-step, and looked forward to and enjoyed retirement. He struggles to engage with this highly connected world, the gig economy, political correctness, mental health and trauma – it’s changing too fast and it’s difficult to keep up.

Pip and Pop, as it turns out, have complementary strengths and weaknesses. They have a lot to learn from one another, but the only way they can both benefit is if they create a space to listen to one another.

Lessons from Pip and Pop

It is remarkable what I’ve learned so far in my exploration of Pip and Pop, and it’s all stuff that books and videos simply cannot teach you. Some lessons are just re-affirming what I already knew, but others were complete surprises that only revealed themselves to me because of the practical nature of the learning method.

I know these ‘final’ images have broken a lot of the rules of comics. The contrast isn’t great, the colour palettes could be better, the drawing isn’t as crisp as I would like. The list of imperfections goes on. But getting them perfect was never the point. Going through the process of writing a comic – construction of humour and timing, panelling it out, gridding and inking, attempting typography, understanding the value of traditional and digital approaches to colouring, it’s all contributed to giving me a more profound appreciation of the professionals I admire, but also a desire to keep pushing myself to understand the medium through practice, not theory.

Beyond the practical understanding of what it takes to create a comic, Pip and Pop are still helping me answer questions. Not just on the page, but in life. Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin and Hobbes, talks about how he doesn’t feel that he’s making Calvin or Hobbes do anything, because they have a life of their own. Pip and Pop are giving me a similar feeling. They are with me in every conversation I have with people who are younger than me and people who are older than me. In some cases, I hear Pip and Pop speaking, not the person I’m speaking to. That’s a profound shift in cognition based on a bit of time spent with pencil and ink.

It’s something that most people won’t notice, but Pip and Pop have shifted, in subtle ways, the way I think about and create my picture book work – mainly about the way I think about colour, but also the way I think about visual storytelling. This experiment is unlikely to end up anywhere, and I’m OK with that. That was never the point.

The most important lesson I’ve learned from all of this is that learning anything new is an exercise in vulnerability. It seems that we’re more open to that as children, and less so as adults. As adults, we’re supposed to have ‘figured it out already’ right? What makes it hard is that we have to admit to ourselves (and more importantly, others) that we don’t know something and that the most likely outcome is that we’ll stuff things up. Over and over again. In a culture that rewards and celebrates winning over failure, that’s hard, at least at first. But the universal rule seems to be that those who find a way to be comfortable with failure are the ones that end up winning in the long run when winning just means answering the most important question we’re here to answer – understanding who we are in a deeper way which, when you think about it, is the whole purpose of making the art we need to make.