The law of diminishing returns is an economic law stating that if one input in the production of a commodity is increased while all other inputs are held fixed, a point will eventually be reached at which additions of the input yield progressively smaller, or diminishing, increases in output.

In English – at some point, doing more or throwing more at something doesn’t necessarily get you more.

When to stop?

It worries me when I hear illustrators say, “I’ve done 99 versions of this drawing to get to the right one.” Really? There wasn’t a single ‘good enough’ drawing in the first 10? Or the first 5? At the same time, I also hear illustrators say, “I can’t get enough spontaneity in my work.” And, well, after 99 tries, isn’t it clear why?

Illustrators constantly seem to be navigating this space between ‘spontaneity’ and ‘perfection’. We have a vision in our minds of what we want to achieve with a drawing but something gets lost in translation when our hands and eyes start to work together to try and get it down on paper. Our expectations are always ahead of our ability to meet them. If it wasn’t that way, we’d just stop making. And so, having felt a sense of failure at the first attempt at achieving that vision, we try again, and again, and again, until we’re looking at 99 versions of the same thing.

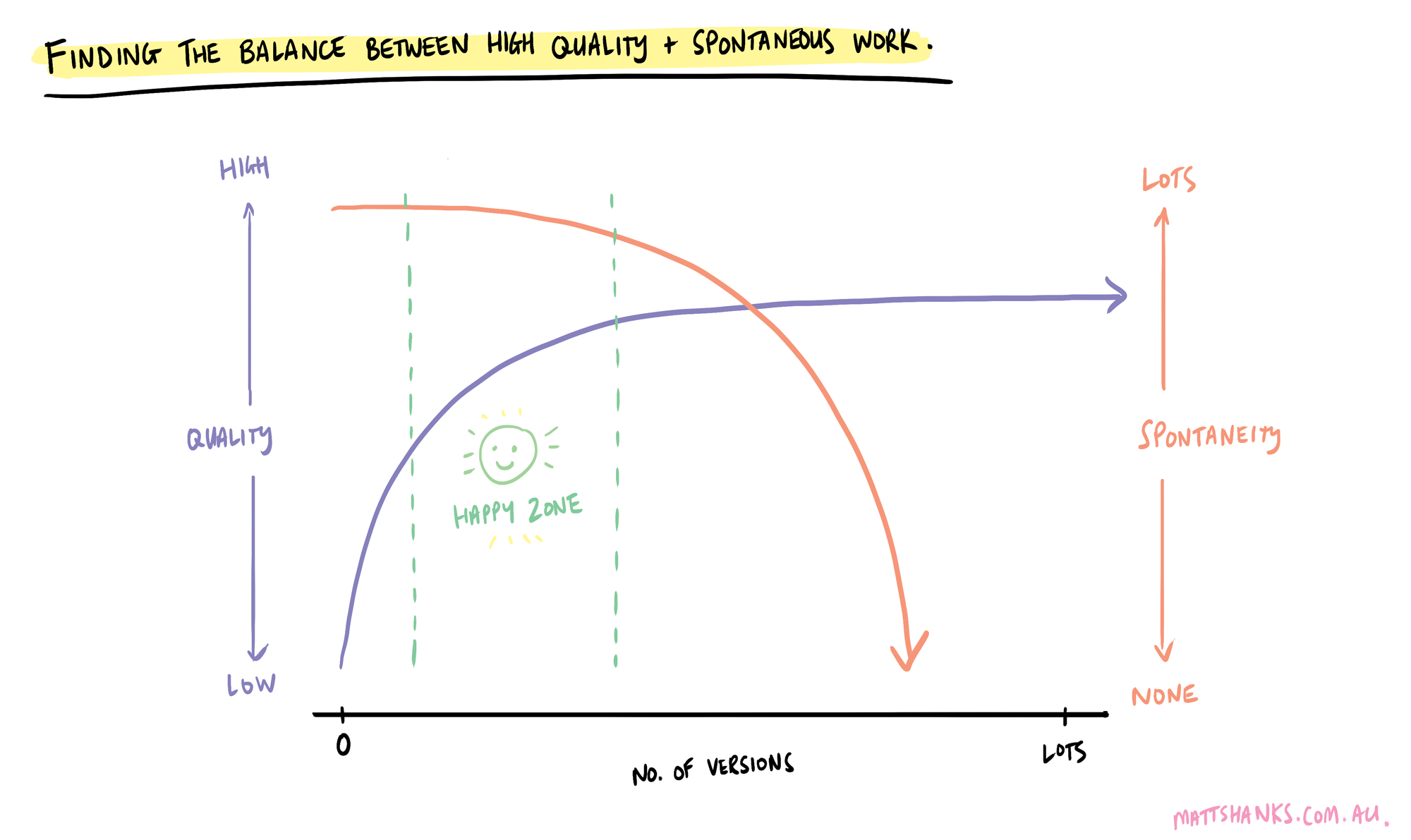

I can’t help but think that the law of diminishing returns applies to illustration. At what point, during the accumulation of illustration after illustration, do we stop? Sure, iteration leads to improvement – every version is a draft, after all – but why do we stop at 99 and not 10? or 5?

Calibrating to ‘the other’

Over the years, I’ve learned that others don’t see what I see. What bothers me doesn’t bother others. In fact, often what bothers me is the stuff that others *love* – the *imperfections* and the mistakes. Could someone who isn’t me tell the difference between attempt no. 3 and attempt no. 99? With each attempt, does the spontaneity degrade? Where’s the happy middle? Who are we illustrating for anyway?

I don’t know if 99 or 3 is the magic number. Maybe it’s different for each person and each drawing. But, at some point, it’s useful to remember that I’m not the audience when I’m making a book, the reader is. The ‘artist’ must give way to the ‘designer’ at some point – the question isn’t “Is this drawing good enough?” the question is, “Does this drawing give the reader what they need?” When we set our limits by someone else’s standards, and seek feedback from them early, it’s easier to know when enough is enough.

If we spend less time creating 99 drawings of the same thing to try and get to perfect, maybe we get more time to create 1 spontaneous drawing of 99 different things. I know which one I’d prefer, and which one my audience would prefer, too.