There’s this concept in improv theatre, a rule of thumb; it’s called ‘Yes, and’ thinking. The purpose of ‘Yes, and’ is to accept someone’s line of thinking (the ‘yes’ bit) and then build upon it (the ‘and’ bit). When you experience a really incredible improvised theatre performance, it’s often (at least partly) because the actors are using ‘yes, and.’

In improv theatre, you don’t know where the story is going to go. It’s not something that’s planned to the nth degree. There’s no script, no storyboard. It’s what makes it so fun. It always starts with a question, or a statement or a scenario, but where it goes from there is up to the actors. “Yes, and” encourages growth and play. It embraces the uncertainty not as a thing to be challenged or removed, but an advantage or a feature of the format. It removes early judgement. It’s what separates it from non-improvised theatre.

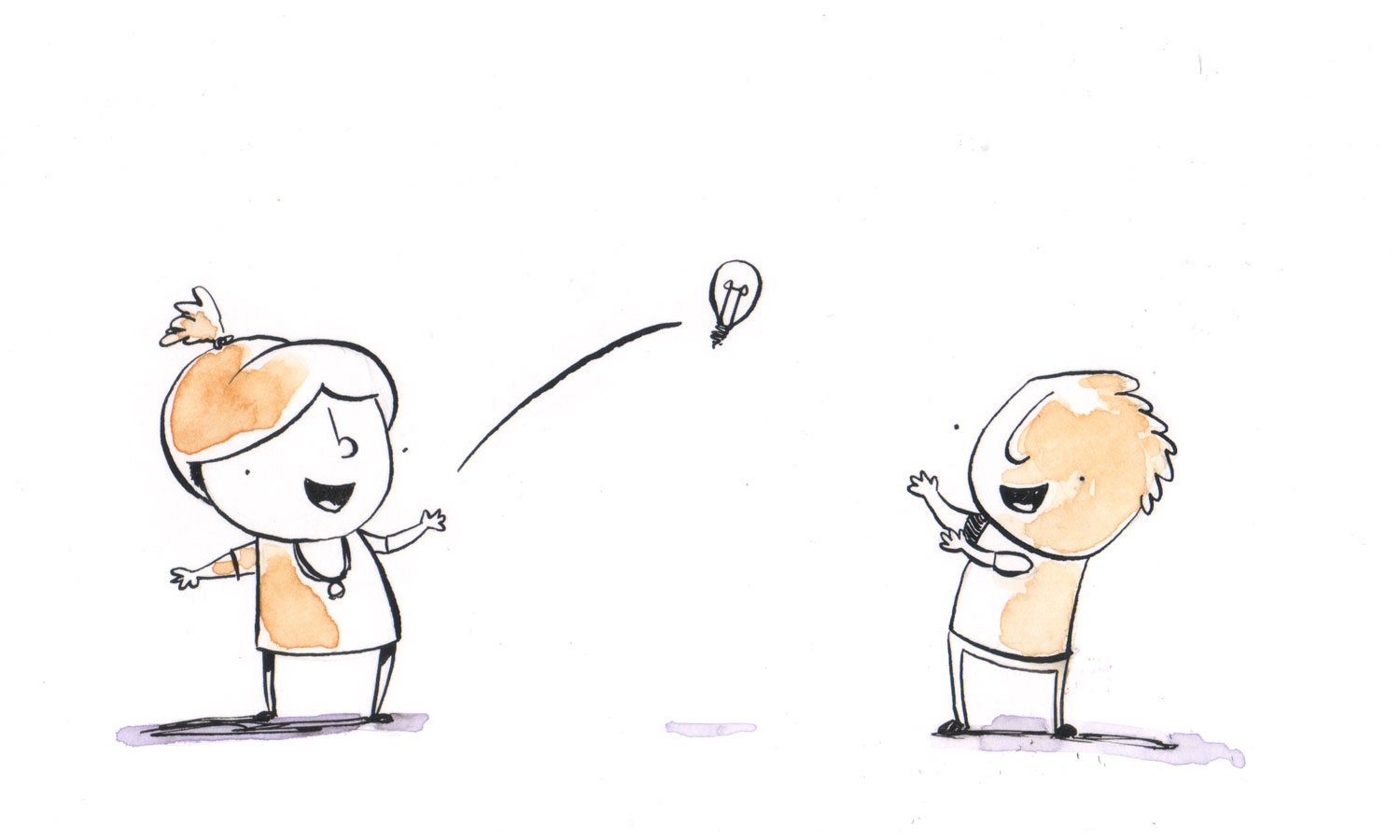

Consider this scenario. Two actors, one playing a patient, the other playing a doctor.

PATIENT ENTERS DOCTOR’S OFFICE.

Patient: Doctor Doctor! Please help me! I’ve swallowed a sparrow and now whenever I speak, I can’t help but cheep. CHEEP!

In a “yes, and” environment, the Doctor now builds upon that idea.

Doctor: Oh my goodness, a sparrow! I’ve seen this before. Do you have an uncontrollable craving to eat worms or seeds yet?!

Can you see the ‘Yes, and’ here? The doctor acknowledges the situation, “A sparrow!”, and then builds upon it using their role as a doctor. A doctor normally diagnoses by enquiry of symptoms, so they think, ‘well, what other symptoms might there be if a person ate a sparrow’.

The actor playing the patient had no idea where the story was going when they setup this zany scenario, but with some simple “yes, and” thinking, the story has moved on, it’s become immediately more interesting. No one owns it now. The Doctor didn’t say, “No, but that’s just stupid! Whoever heard of such a ridiculous thing.” There’s no judgement. That can come later. And now, with this idea of worms and seeds, it’s up to the patient to apply their own ‘yes, and’ to expand on it.

Patient: Oh my goodness Doctor, Yes! I do have an unusual craving for seeds. And sometimes, when I burp, feathers come out.

… and so the story evolves.

Like in improv theatre, picture books always start with a scenario or an idea. A protagonist is in an environment where there’s some sort of conflict to overcome. Some authors are more prescriptive than others, but the best picture books texts are loose and open. There’s a space in them. Room to move. They offer a scenario, and invite the illustrator to respond. The parallel between our patient and doctor scenario is clear.

When you pick up a picture book, the relationship between author and illustrator is evident most of the time. There’s a stiffness to the work when the illustrator just ‘illuminated someone else’s vision’. But if both actors have contributed equally to evolve the story, or the character, or the environment, whatever aspect of the book that really makes it sing, the whole thing feels unified. As a reader, you get lost in that world and, well, that’s just the magic of books, isn’t it?

One of the great joys of working on picture books, like improv, is the uncertainty. Not having all the answers up front. The possibility of getting to a point where the final story has evolved in to something neither of you could have come up with on your own.