One question I get asked a lot is ‘how long does it take for you to make a picture book?’ I understand why people want to know, but I can’t help but think it’s the wrong question with what is likely to be an unhelpful answer.

I know that I can knock out a fairly competent editorial spot illustration in about an hour. A storyboard for a 32-page picture book will take me a weekend. A picture book spread averages out at about 2 hours, give or take the complexity of the scene. The final art takes about 4 hours per spread.

Now that I’ve said that, another artist reading will have one of two responses. The first response is “Wow, that’s so much faster than I can do it, I’m so slow”. The second response is, “Wow, that’s really slow, I’m heaps faster than that.”

Does the comparison matter?

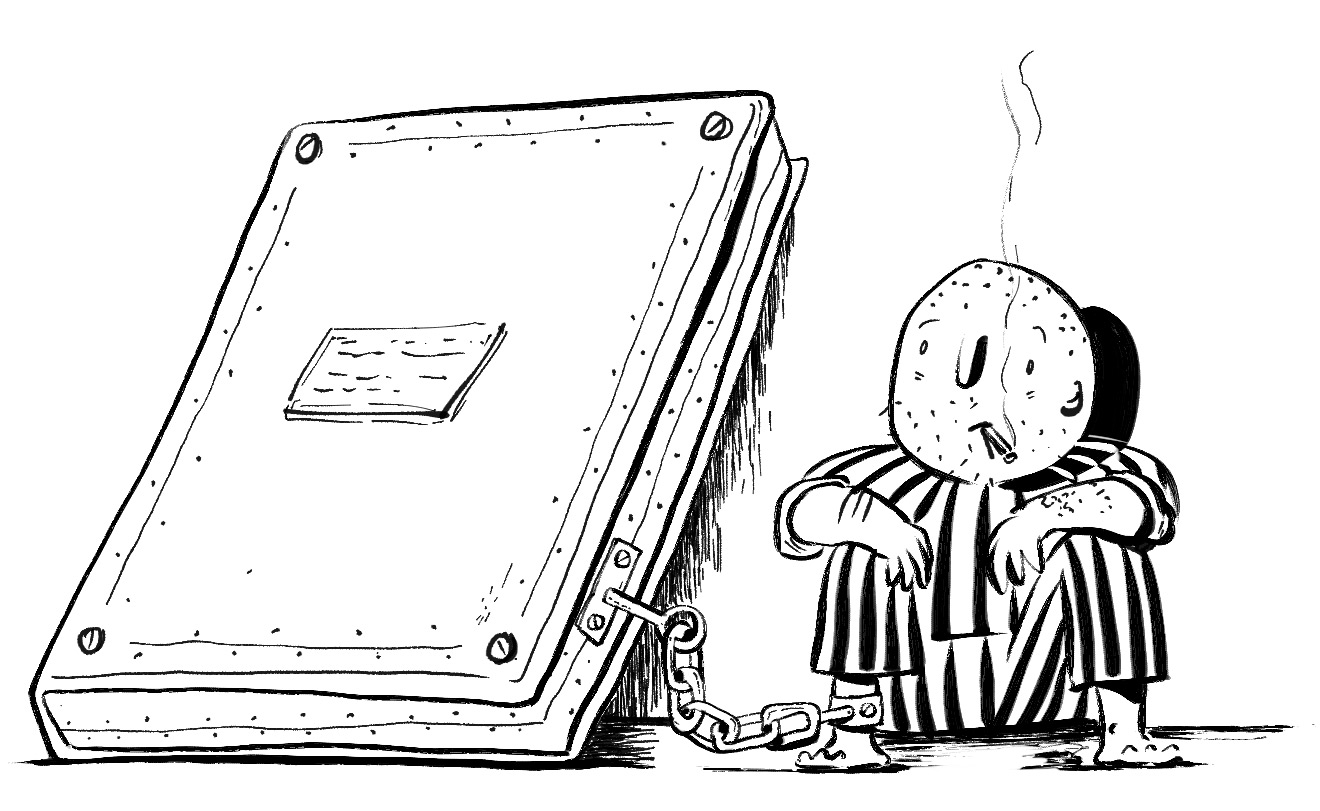

But, there’s a lot that goes unsaid in the response to the question. Do you mean elapsed time (which includes waiting for paint to dry?), or do you mean active time (the time I spend actually putting brush and pencil to paper?) By the way, which mediums are we talking about? Pencil? Watercolour? Oil? Acrylic? Mixed media? Which ones do you use? Which ones do I use? They all have an inherent relationship with time.

If I gave a response to ‘how long does it take to make a picture book’ that was twice as long, or half as long, what difference would it make?

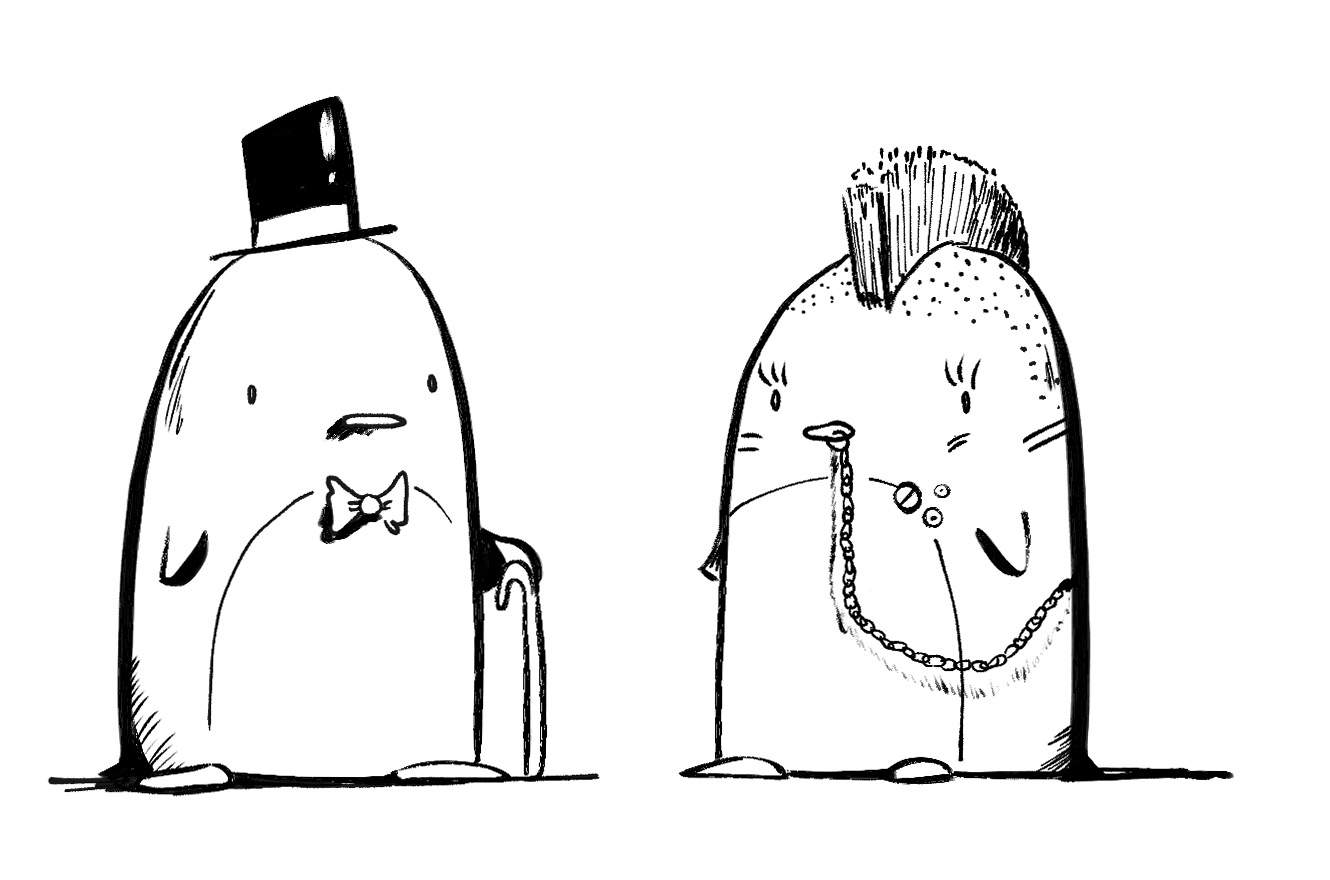

Humans tend to equate effort with quality (i.e. The Effort Bias). People will tend to value a drawing more if I said I spent 12 months on it as opposed to 12 minutes. So, knowing this, I could make another artist think whatever I wanted them to think by answering the question of ‘how long does it take to make a drawing’ in whichever way suited my self-interest. Maybe Bruce Whateley’s “Ruben” took just as much time as “Eric the Postie”. Does that make one better or worse?

Things aren’t slow, we just imagine them to fast.

Whilst it helps our meagre human brains to think about things in time, effort, and quality, there’s often very little relationship between those things when it comes to art-making – especially when we’re trying to use those things to compare ourselves to others. Some of us need to labour over a drawing for 12 months. Some of us get the ‘divine inspiration’ and a drawing falls out on to the page in a matter of minutes.

A better approach might be to focus on the most authentic work we can make for ourselves, regardless of how long it takes. Instead of ‘how long does it take?’ maybe a better question is ‘why did you make it?’ or ‘what did you learn from it?’ If the work we make is about helping us learn more about ourselves – sometimes some lessons take longer than others and that’s OK.